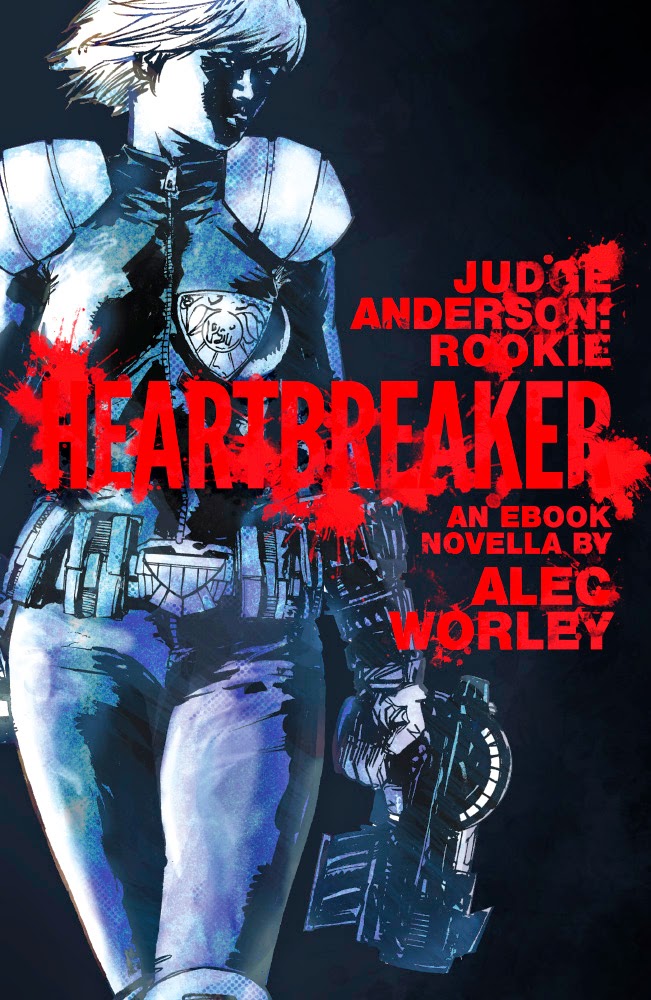

Last month Alec Worley launched our latest 2000 AD tie-in series with his new eNovella Judge Anderson Rookie: Heartbreaker, a brand new prose title which saw us taking readers back to veteran Psi-Judge

AB: SO WHAT’S ‘JUDGE ANDERSON: HEARTBREAKER’ ABOUT?

AW: Like the Dredd: Year Zero books, this is set during the character’s first year after graduation. So at this point Anderson is still fresh out of the Academy of Law and getting to grips with life on the streets. You don’t need to know anything at all about Anderson’s history from the comics or even the movie. You can just dive right in and meet her for the first time.

Anyway, about the story: Anderson is on the trail of a telepathic killer who has been selecting victims via ‘Meet Market’, Mega-City One’s premier dating agency – a sort of cross between eHarmony and eBay. Anderson has to go undercover and bring the murderer to justice before the citizens attending the upcoming Valentine’s Parade find themselves smitten with something even deadlier than love.

AB: WHY DID YOU CHOOSE TO WRITE ANDERSON INSTEAD OF DREDD?

AW: Anderson’s one of my favourite 2000 AD characters. She’s just awesome. In those early stories she’s so full of life, such a perfect foil for Dredd. I just really, really wanted to write her. But also, prose is perfect for getting inside a character’s head and I think the effectiveness of Dredd’s character lies, for the most part, in you not being allowed inside.

With this story, I know a lot of readers will be coming to it from having watched Anderson in the 2012 Dredd movie, so I wanted to apply that grimy procedural feel to the world of the comics in which this is set. But I also wanted to make Anderson more sure of herself than she was in the movie and show what she’s made of right from the beginning. This may be her first year on the street, but she’s no pushover. I really wanted to emphasise her strength, smarts and determination as someone who’s survived 15 gruelling years of life-or-death Judicial training. Despite her ‘rookie’ status, she doesn’t need to prove herself to anybody. She’s a Judge!

I’m fascinated by the idea of what it might be like to be psychic. Make that character a cop and you can really go to town. This is a woman who can literally hear what people are thinking. How does that work exactly? What does it feel like? How would that affect you as a person and your view of everyone around you? When I was pitching ideas, I found this article I’d read about online dating and got imagining about how you could take that to an extreme in the crazy world of Mega-City One. Straight away that suggested all these cool conflicts and ideas about how people relate to each other. A psychic like Anderson was perfect for that setting. I’m not sure I could imagine Dredd going undercover at dating agency!

AB: DREDD IS A NOTORIOUSLY TOUGH CHARACTER TO WRITE. WHAT WERE THE CHALLENGES OF WRITING ANDERSON? HOW DO THEY DIFFER?

AW: Dredd needs more contrast, I think. You have to have these contrasting supporting characters or else place Dredd in situations that bring out just how much of a badass he is. Let’s face it, all Judges are hard-as-nails law-machines, dedicated to nailing perps, so Dredd stories have to dramatise just how dedicated and ruthless Dredd is compared to everyone else in the Department. Anderson is more human, more volatile and unpredictable, and as soon as I started writing her I realised that I had to come up with a very specific way in which she perceives the world.

The fact that she’s psychic also makes her a nightmare to deal with when it comes to plotting. This is another way in which magic and the supernatural can poison a story if you’re not careful. Scenes often rely on characters withholding information from each other, so Anderson has the potential to kill a scene stone-dead the minute she walks into it. If Anderson was the detective in, say, Chinatown or Silence Of The Lambs, the movie would be over within ten minutes. And this story had to be a whodunit, which presented so many difficulties when it came to breaking down the story. I can see now why so many of Anderson’s adventures in the comics tend to be action-adventure or psychedelic supernatural stuff where her psi-talents have less opportunity to directly impact the story.

AB: THE SCENES WHERE YOU’RE DESCRIBING HER READING PEOPLE’S MINDS, RETRIEVING THEIR MEMORIES AND SO ON, WORK REALLY WELL. HOW DID YOU COME UP WITH THEM? WAS THERE A LOT OF RESEARCH INVOLVED IN THE BOOK OVERALL?

AW: Loads. I read a lot on neurology and dug out of lot of New Scientist articles about how the brain works, how memories work and wotnot. Of course, there’s a lot of poetic license, and I used it really as a starting point. The thing is you have to articulate all this stuff. When you have Anderson reading people’s minds or engaging in psychic duals in the comics you can have all that wonderful Boo Cook-style phantasmagoria. You know, brain-waves radiating off her, weird images bursting from her head, all that stuff. But how do you express that in prose? Unless you can describe exactly what she’s going through, a psychic dual ends up more like a staring contest! Plus, there’s different kinds of psychic in the Dreddworld – telepaths who can hear thoughts, empaths who can feel feelings, and so on – so different psychics perceive things in different ways.

I was also reading a lot of non-fiction about police tactics and procedure, including David Simon’s Homicide, which is just amazing, beautifully written and full of detail. Reading this stuff I was thinking about how a psychic would read that room or conduct that field interview.

I think real world details have become increasingly important in Dredd. It’s a series that’s become steadily rationalised over the years, which has probably got a lot to do with the aging readership. But it’s a very tricky balance trying to bring a sort of adult rationality to something that was dreamed up for the amusement of little boys in the ‘70s. I think ‘realistic’ and ‘believable’ are two different things, but, for me, you can make a story both if you just see the world through the character’s eyes, which is an even more interesting proposition with a character like Anderson as she’s seeing the world through everyone else’s eyes too.

AB: THE FIGHT SCENES IN THIS REALLY STOOD OUT. I’M NOT SURE WE’VE EVER SEEN ANDERSON GET QUITE SO HANDS ON IN THE COMICS…

AW: Again, I wanted to bring in the grittiness of the movie. In the comics, I guess all these sort of kickboxing moves look pretty cool, but I wanted the fights in my story to be more real-world. All this came about just by thinking through who she was, thinking through the way cops and marines fight. It’s all elbows and chokeholds and it’s over in seconds. Plus, I’d just seen the Gina Curano movie Haywire and loved it. But you can’t put that sort of technical fighting in 2000 AD as it eats up too many panels. So again, prose proved ideal. My best friend does MMA. He’s also a massive geek. I showed him a picture of Olivia Thirlby and asked him if a woman of that build and height take out a room full of guys if she knew what she was doing. ‘Absolutely,’ he said and spent the rest of the evening showing me exactly how. I tried to get as much ferocity in there as I could without it getting too technical. It’s also less about how she looks and more about what she can do.

AB: TO SUM UP, WHAT’S YOUR TAKE ON ANDERSON?

AW: I see Anderson as someone who – despite the Academy’s efforts to drill all these things out of her – is cheeky, hip and full of wisecracks and often struggles to keep her thoughts to herself. She can also be laid back to point of being cocky. She’s changed an awful lot since she first appeared in 2000 AD, but I’ve always seen her as someone who believes the city is worth fighting for and not just out of a robotic sense of duty like Dredd, but genuine compassion. She’s a brilliant character and I think she’s a terrific entry-point into the world of Judge Dredd.

***

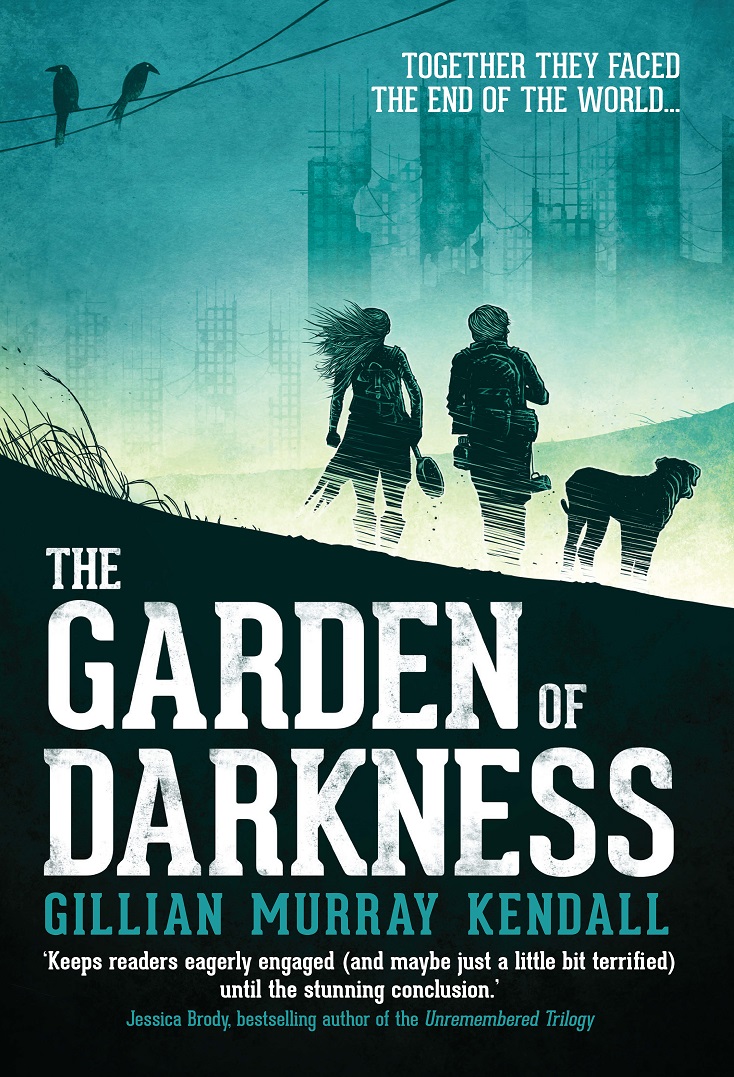

Mega-City One, 2100 AD. Psi-Judge Cassandra Anderson’s first year on the streets as a full-Eagle Judge.

After a string of apparently random, deadly assaults by customers at Meet Market – Mega-City One’s biggest, trashiest dating agency – Anderson is convinced a telepathic killer is to blame. Putting her career on the line, the newly-trained Psi-Judge goes undercover to bring the murderer to justice.

She’ll have to act fast. Mega-City One’s annual huge, riotous Valentine’s Day Parade is fast approaching, and the killer has a particularly grand gesture

Heartbreaker is out now on the kindle (UK | US) and via our DRM-free eBook store.

About the author: Alec Worley was a projectionist and a film critic before completing his Future Shock apprenticeship for 2000 AD and creating two original series: werewolf apocalypse saga Age Of The Wolf (with Jon Davis-Hunt) and ‘spookpunk’ adventure comedy Dandridge (with Warren Pleece). He’s also written Judge Dredd, Robo-Hunter, Tharg’s 3rillers and Tales From The Black Museum.