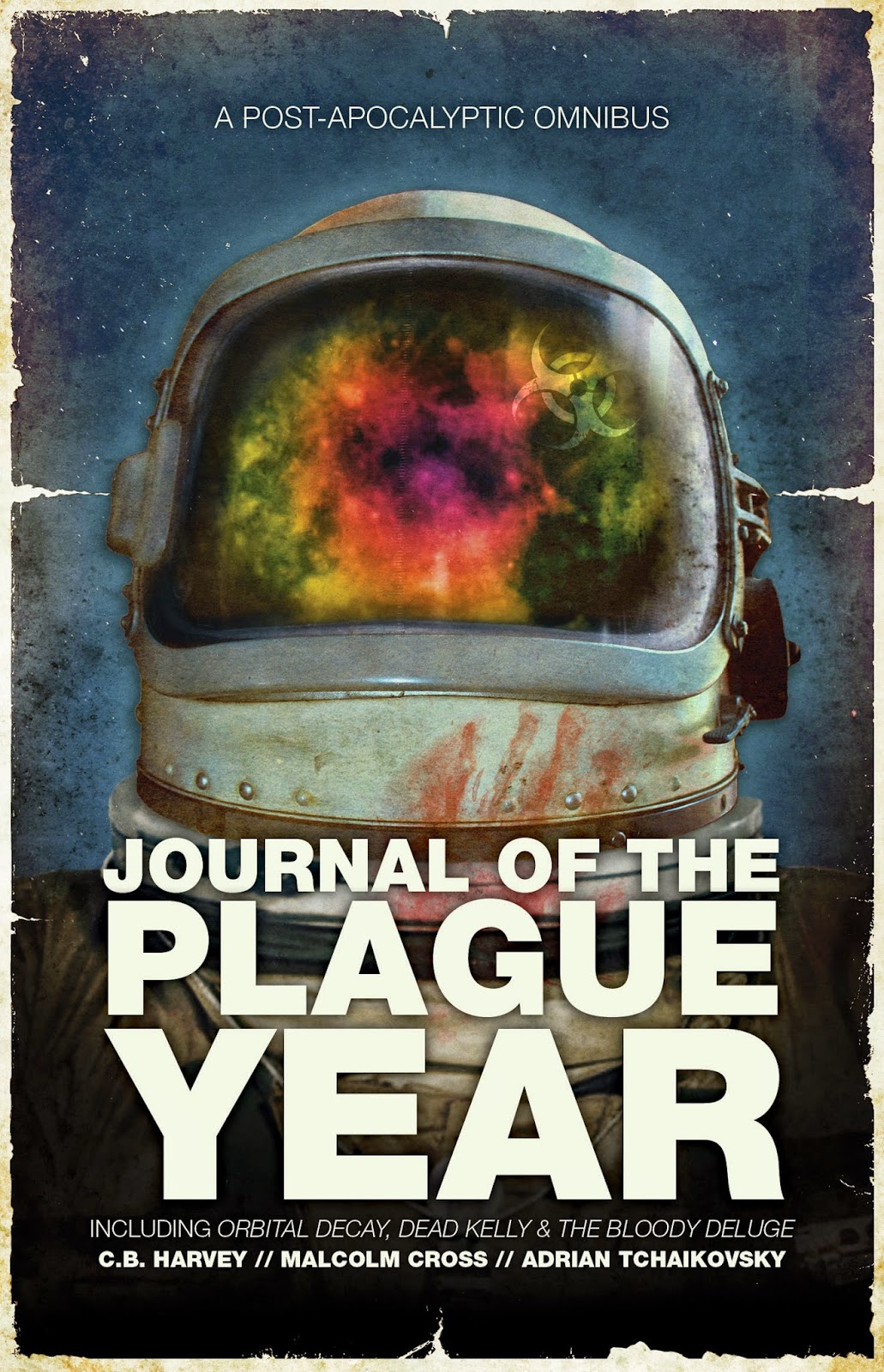

To celebrate last week’s UK release of The Journal of the Plague Year we sat down with Abaddon Editor David Moore to work through the chronology of The Afterblight series so far.

In the Beginning

1. Orbital Decay by Malcolm Cross. This one’s easy, as it starts as the virus is just getting started.

=2. School’s Out by Scott K. Andrews. Exactly where to place Scott’s opening novel is tricky, as Lee flashes back to the early days of the Cull and the story runs out over the course of a year, but I’m going to pin this one down as at least starting within a few months of the virus breaking out.

=2. Dead Kelly by C. B. Harvey. Colin’s contribution is explicitly placed six months after the Cull hits, which makes it more or less contemporary with the start of School’s out.

One Year on

3. The Bloody Deluge by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Adrian doesn’t pin Katy’s and Emil’s flight across Germany down, but it seems to begin between one and two years after the Cull.

Year Two

4. Death Got No Mercy by Al Ewing. Al’s actually quite specific; Cade’s rampage begins two years after the dyin’ started.

5. ‘The Man Who Would Not Be King’ by Scott Andrews. This short story, included with Paul Kane’s Broken Arrow (and the collected School’s Out Forever), bridges School’s Out and Operation Motherland and is set around two years after the Cull.

Year Three

6. Operation Motherland by Scott K. Andrews. Set a while after the end of School’s Out, as the new school has had a chance to settle in, Motherland takes place around three years after the Cull.

Year Four

7. Arrowhead by Paul Kane. Paul and Scott, I gather, sorted out between themselves that de Falaise’s invasion occurs after the destruction of the base in Salisbury plain, explaining why there was no organised resistance. Around Year Four.

Year Five

=8. The Culled by Simon Spurrier. The nameless soldier of Simon’s book explicitly gives the date as five years after the Cull.

=8. Kill or Cure by Rebecca Levene. Jasmine leaves the secret facility at Lake Erie at the same time as her lover – The Culled’s nameless hero – sets out to find her.

=8. Children’s Crusade by Scott K. Andrews. Lee and Matron clash with the Neo-Clergy’s child-snatchers, suggesting that this book is contemporary with The Culled.

9. ‘The Servitor’ by Paul Kane. This short story – published in Death Ray #21, Oct/Nov 2009 (and collected in the ebook edition of Hooded Man) – introduces the sinister new cult that kicks off the action in Broken Arrow. Between Years Five and Six.

Year Six

10. Broken Arrow by Paul Kane. It has been some while since Arrowhead’s Rob Stokes settled Nottingham and established his Rangers, putting this book around Year Six

11. ‘Perfect Presents’ by Paul Kane. A charming snapshot of life in Afterblight Nottingham, this short story – featured in Abaddon Books’ A Very Abaddon Christmas blog event, 2009 (and collected in the ebook edition of Hooded Man) – is set the Christmas after Broken Arrow.

Year Seven

12. ‘Signs and Portents’ by Paul Kane. This short story – included in Children’s Crusade (and collected in ebook edition of Hooded Man) – sets the scene for Arrowland, and takes place in about Year Seven.

Year Eight to Year Nine

13. Arrowland by Paul Kane. A little while has passed since the rise and fall of the Tsar, putting this book at about eight or nine years after the Cull.

One Decade on

14. Dawn Over Doomsday by Jasper Bark. Some years have passed since the Apostolic Church of the Rediscovered Dawn was crippled by the nameless soldier of The Culled in Year Five, placing it about one decade in.

Twenty Years on

15. Blood Ocean by Weston Ochse. This one’s made fairly easy by dint of sheer scale. It’s not clear when exactly the events occur, but it’s clear that people have been born and grown to adulthood never knowing a world before the Cull. Blood Ocean’s set at least twenty years after the virus.

With each new title and each new author bring a whole new perspective and history to the world of The Afterblight we’re already really excited to see what the next wave of books brings.

Journal of the Plague Year is out now: UK | US | DRM-free eBook