With seeing “Best Beloved” go to print, I also see it as a pleasant, necessary, affirming, but also weird transition in my life. It’s a signal to me that I no longer have to resort to cultural appropriation in order to get others to read my work.

Of course, most of the people over the years that saw me culturally appropriating didn’t think what I was doing was bad. In fact, they encouraged me, and told me that I was probably doing the right thing, and helping myself along. They didn’t even feel that what I was doing was cultural appropriation and was, simply, “appropriate,” because I was a visible minority writer who was telling stories about white people, even though I wasn’t white myself.

As a member of Generation X, that was just the way it was when I was a kid. If you’re a Filipino nerd growing up in Canada during the Disco and New Wave eras of music, the science fiction and fantasy you read is not going to have you in it. So you make do. You thrill along with the all-white kids in Derry, Maine, in It, and you get swept up in the heist-hijinks of Caucasians Case and Molly in Neuromancer, and you cheer them on, identify with them, and empathize with them because you don’t have a choice. You’re not going to see an East Asian, or South Asian or African protagonist in science fiction, fantasy, urban fantasy or horror. Not during the time of Walkmans and car phones.

So when I finally took to telling my own stories, I told the stories I was most familiar with; white people doing heroic things. I was aware of the convention or tradition of having “ethnic characters” who looked like me portrayed as amusing or unflattering, so I simply kept myself and people like me out of the stories I wrote, so I wouldn’t have to do that to myself. But there was never any question that by choosing to write about Western characters I was doing the “wrong” thing. My natural inclination to embrace Caucasian men and women as central characters was acknowledged as proper. My choice was an indication of my willingness to tell “real stories,” and I was rewarded for this with my first sales in Canadian genre magazines that validated my decision. No one in North America wanted to hear me tell a story about me, or my people, they wanted me to tell a story about “them,” and about why they continued to matter.

Things have changed. A lot.

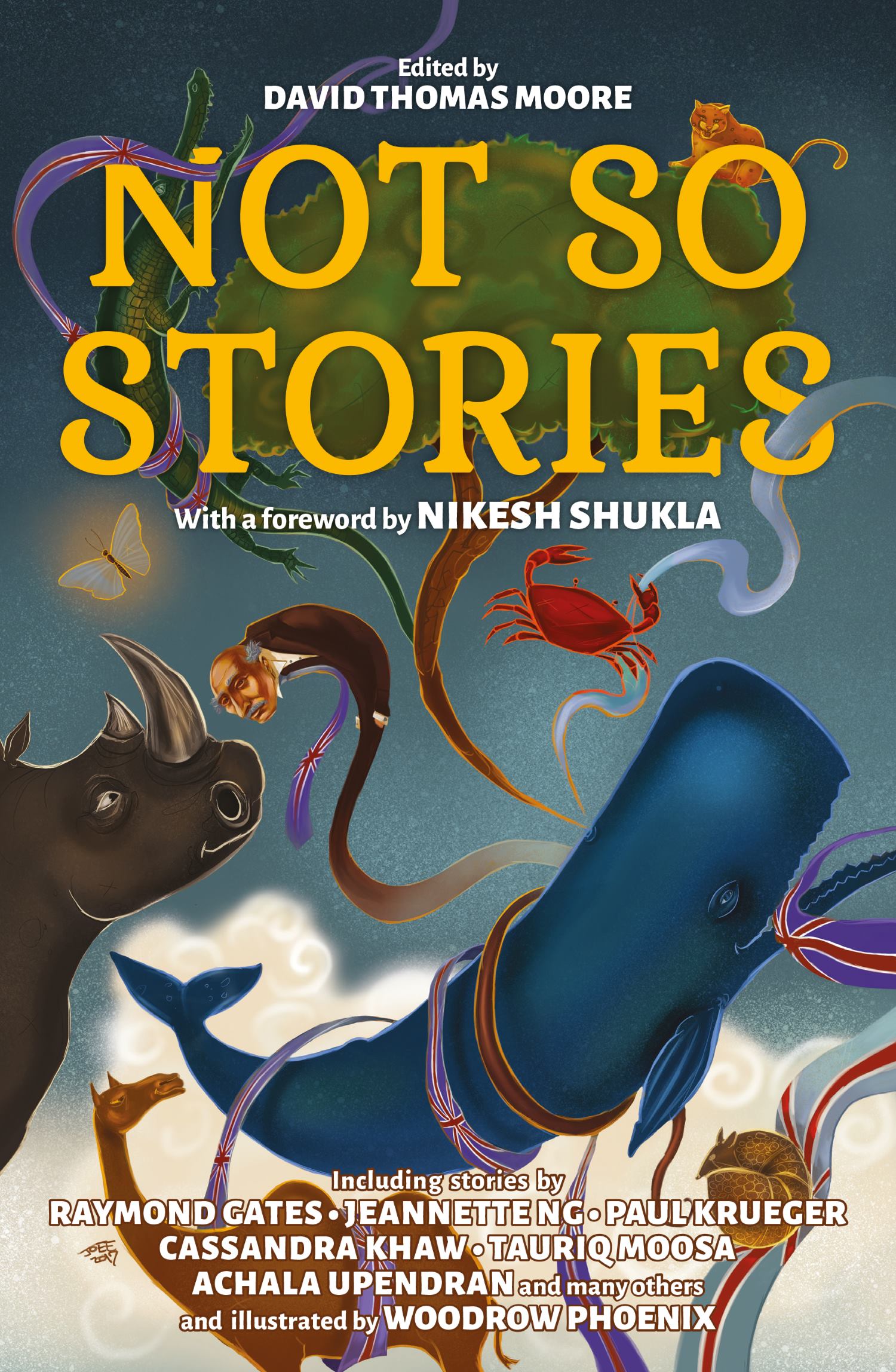

When I was asked if I’d like to contribute to Not So Stories, I was, of course, frightened to death at being included in an anthology with a lot of very talented, established writers when I myself wasn’t. But beyond that intimidation, I was also very happy to say yes, and in some ways, felt personally, morally obligated to do so. After years writing myself and people like me out of my own stories, I’d made the decision a few years ago to stop that. I realized that if I needed to tell stories for myself that kept myself out of them in order to be considered “legitimate,” then maybe I didn’t want to succeed that way.

Being invited to contribute to this anthology was part of a path for me that validated that decision. Putting people like me into stories didn’t make them less legitimate. And people who complained that my stories might be more problematic because they couldn’t see themselves in my stories… well, that’s how I grew up. I didn’t have a choice, so I adapted.

Maybe it’s time for others to adapt too. Countries like Canada and the United States are changing. They are slowly, but inevitably transitioning to a demographic where even though everyone is American or Canadian, that majority may no longer be of Western descent in a few generations. So while it’s true that anyone Asian that wants to “see themselves” in literature or film can simply retreat back to Asia to consume that media, that’s not the same as being a person who has lived and grown up in an American or Canadian society, and wants to see themselves in that society, the one they actually live in.

So I’m very pleased to be a part of this process, and even if I’m not one of the Big League writers that was asked to contribute to the Not So Stories anthology, I’m touched and honored that I would be allowed to keep company with them. We all have something to say about who we are, and it’s a relief that the message no longer has to be white washed.

Not So Stories is out from Rebellion this month! Click the links below to Pre-order…

Not So Stories is available for pre-order now!

Pre-order: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Google|Kobo|RebellionStore