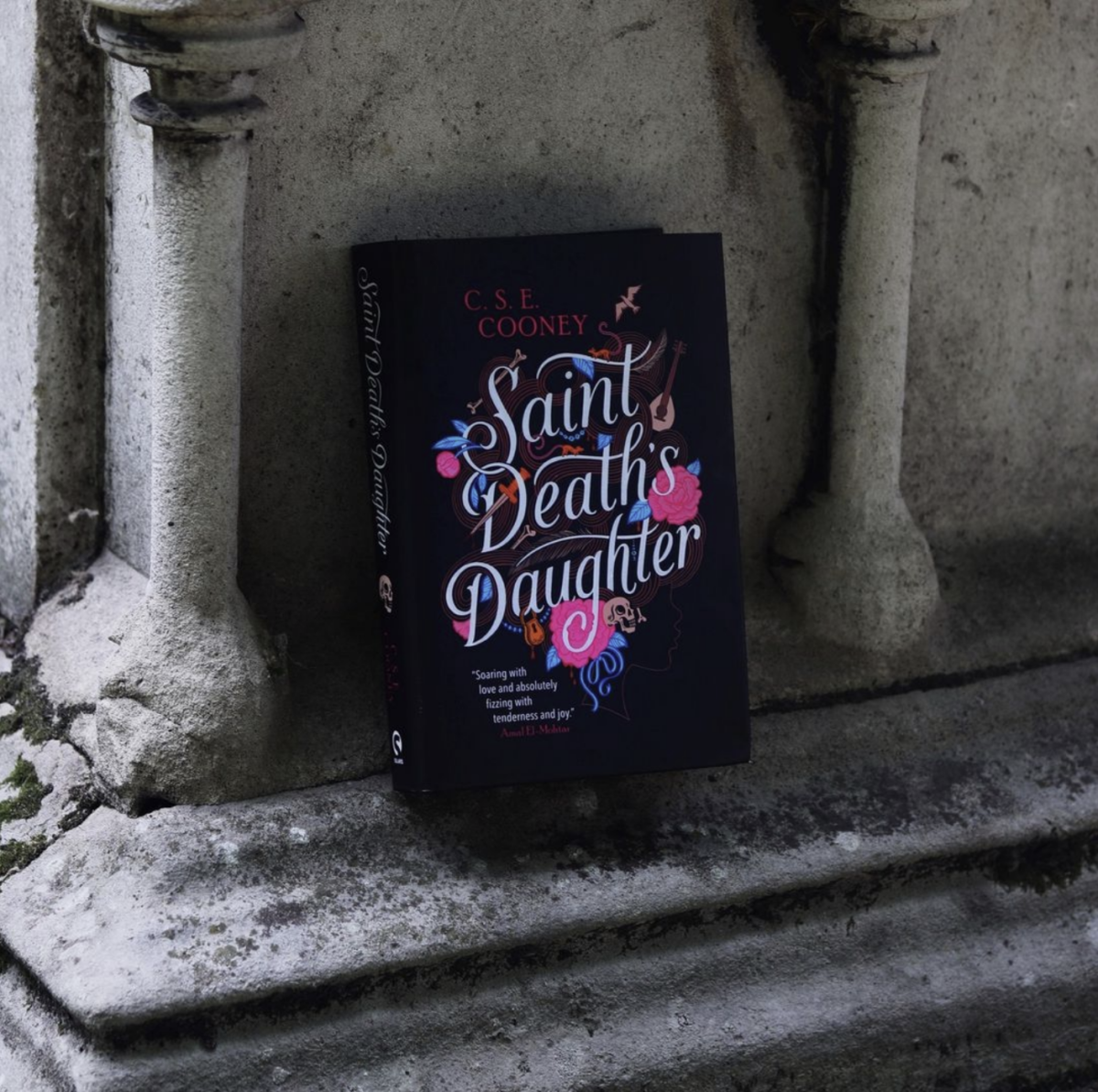

Why Necromancy? C. S. E. Cooney on Saint Death’s Daughter

23rd October 2022

As the spookiest time of the year approaches, we asked C. S. E. Cooney to tell us why she was inspired to write about necromancy in her stunning debut, Saint Death’s Daughter…

Author Sharon Shinn once said: “We all have our things we write about. You write about death. And what comes after.” She said this just after my collection Bone Swans came out.

I admit, I got a little salty at that. I went right for a rebuttal. I was going to cite my sources, quote my texts. So I stopped and counted up all the stories in Bone Swans that were “about death and what comes after.”

Four out of five. Sharon Shinn got me.

And, of course, I’d been writing my novel Saint Death’s Daughter for longer than any of the Bone Swans stories had been around. She hadn’t even read that one, and it was about a freaking necromancer, so.

I started Saint Death’s Daughter to answer a particular “what if” question that tickled me: “What if you have a character who grows up in a family of assassins who is allergic to violence?”

The greater “what if” is genre-specific. What if we have an epic fantasy with a protagonist who cannot—physically cannot—solve her problems with violence? Epic fantasy often revels in violence as a solution. Or, if it doesn’t revel, it at least perpetuates the idea that a climactic and bloody clash between two opposing forces (pivoting on the protagonist and their choices) is unavoidable.

It was a knotty enough “what if” to keep me puzzling at it for twelve years. And in the end, I was only partly successful.

My protagonist can’t get mad and hit people. Not without consequences: she gets an “echo-wound,” a painful mirror of the hurt she inflicts, reflected upon her own person. And echo-wounds don’t just happen when Lanie hits people, either. If anyone near her commits a violent act in her presence, or talks about having done so, or threatens to do so in the future—heck, if Lanie Stones even touches an object that has recently bashed, beaned, or beheaded someone—she will have an allergic reaction to it. This can be anything from nosebleeds to projectile vomiting to losing consciousness.

She has strong motivations for peacekeeping. For her, it’s survival.

There are many violent aspects to this book. There are indulgent passages about weaponry, gleeful footnotes about decortication via oyster shell, and the various and sundry sudden (or otherwise) deaths suffered by the infamous Stones family. But Lanie Stones herself is gentle. She’d prefer to run and hide than stay and fight. She’d prefer to wait tables and read books than solve national crises.

Also, she loves the dead. She can’t help it. If she didn’t have living friends constantly pulling her back out into the sunlight, she’d live in the catacombs and commune only with the non-living natives of her fair city. Love of the dead—and the reciprocal love that the dead give her—makes her powerful. Lanie Stones is a rare thing: a priest of Doédenna, god of Death, in a world where all priests are wizards. Her early allergy to violence was a sign of Saint Death’s favor: that Lanie was destined to be a necromancer. After all, is there any more natural an evolution of a violent reaction against violence than the overturning of death itself?

I don’t believe in life after death (except, perhaps, in the microbial and memorial senses). But I do believe in gentleness. Ultimately, I find the stabby-stabby stuff of epic fantasy, while choreographically appealing, ethically tiresome. I could use a little less problem-solving via edged weapons and uppercuts and world wars, and more creative problem solving by people whose priorities are deescalation and diplomacy, people who, when their backs are to the wall and they finally snap under the enormous, bloody, violent, terrifying forces around them, have yet enough infrastructure of a loving community in place to call them back from the brink of destruction and set them on a path of healing once again.

A fallen family of assassins, divine necromantic powers, tombs full of skeletons and the girl who can wake them: these are all ways of engaging not just with the idea of death, but what it means to be alive. When Lanie Stones finally turns around and confronts her ghosts head-on, she realizes, for the first time, that those who came before her—her cruel teachers, her vicious ancestors—were not always better or wiser or even right. She learns, to her surprise, that what she has always accepted as truth she must now unlearn.

As a writer, I found in Lanie Stones an aspirational character: someone who finds power not in surrendering to authority-sanctioned, historically-approved bloodthirsty displays of might, but in wading counter to it, standing against it, choosing another way. And that’s why, in a nutshell, necromancy. That’s why I wrote Saint Death’s Daughter.