When approached by David Moore to join, ‘Not So Stories,’ I was in the process of adapting to a new and cruel reality, yet one that was always inevitable. My family had recently bade farewell to the last of my grandparent’s generation, and for my siblings and I, the heartbreak was made more poignant by the fact that our only contact with them for years had been via Skype.

In the blink of an eye, all of our plans to make time and visit them in Iran at some undetermined point in the future dissipated in a haze of pain and regret.

So, as I searched my mind for Kipling’s childhood stories such as, “The Butterfly that Stamped,” the only memories that rang loud were those that I’ll not know again: the unique flavours of love that one can only receive from a grandparent.

However, as an Iranian raised and educated in the UK, the duality of Kipling’s, ‘Just So Stories,’ that blend of love and affection mixed with the racist language of, “How the Leopard Got His Spots,” was always apparent to me. The racism was never something that I considered actively. It was a reality born of the disconnect between my place of birth and where I was raised. Instead, I counted myself lucky and celebrated that as a dual national and bilingual person, I had access to writers like Rumi, Omar Khayyam, Hafez, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton. I felt enriched by them all.

When creating, ‘How the Simurgh Won Her Tail,’ my reaction to the source material was as it always has been. I reminded myself that no person can exist in isolation and that literature belongs to all of us, not only to the culture in which it was written. Ubuntu teaches us that we exist because of everyone around us, and so we ought to be open to one another. As William Uri said in, ‘The Walk from No to Yes,’ humanity has splintered itself into 15,000 tribes, yet with the communications revolution, we’re all in touch with one another. For the first time in our species’ history, we’re at what Uri termed as a big family reunion, with all the conflict that that suggests. Do we allow ourselves to focus on that conflict, or dive head first into the pools of human experience that exist all around us, and belong to each and every one of us.

All 15,000 tribes of humanity have come from the same dust, and to that same dust we’re all going to return. The only thing that matters is the dignity with which we treat each other. Do we learn from each other? Do we share our cultures and our histories with one another? If we don’t, who else is there to share it with? Imagine if all the world had one culture, one language, and one variety of life. We’d die in hours from the boredom of it all. So, I decided, as I had done countless times before, that Kipling’s voice, racism and all, belongs to me as much as it does to any other person on Earth.

I chose to focus on the love depicted by Kipling. I channelled my memories of his stories (and the Princess Bride, because what story about a grandfather telling a grandchild a tale can be complete without the Princess Bride,) and focused on the Sufi idea that we are all of us sparks of the divine and that a grandparent’s love, thousands of miles away and on the other side of the world is as real and beautiful as that which exists in our own hearts.

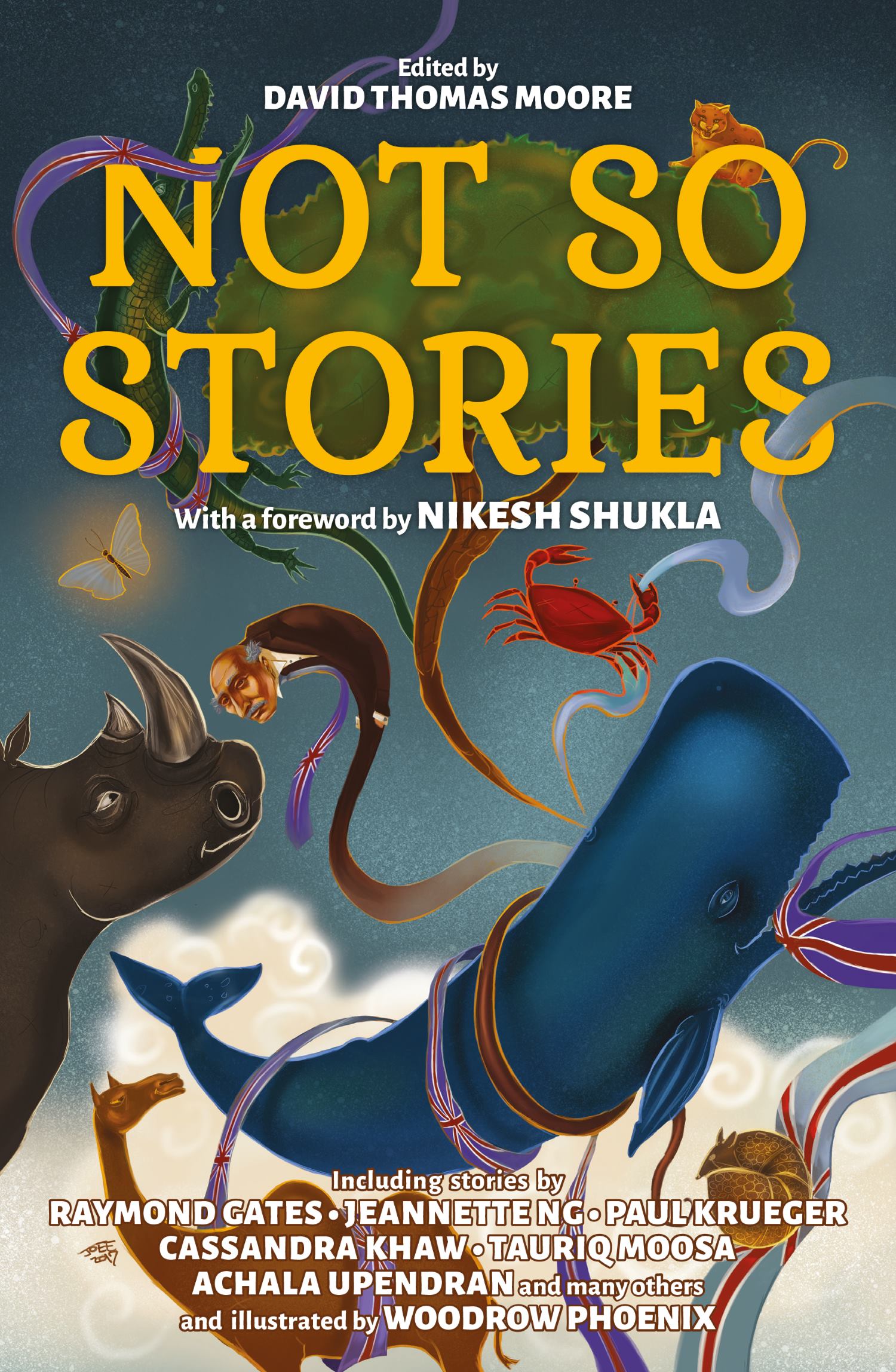

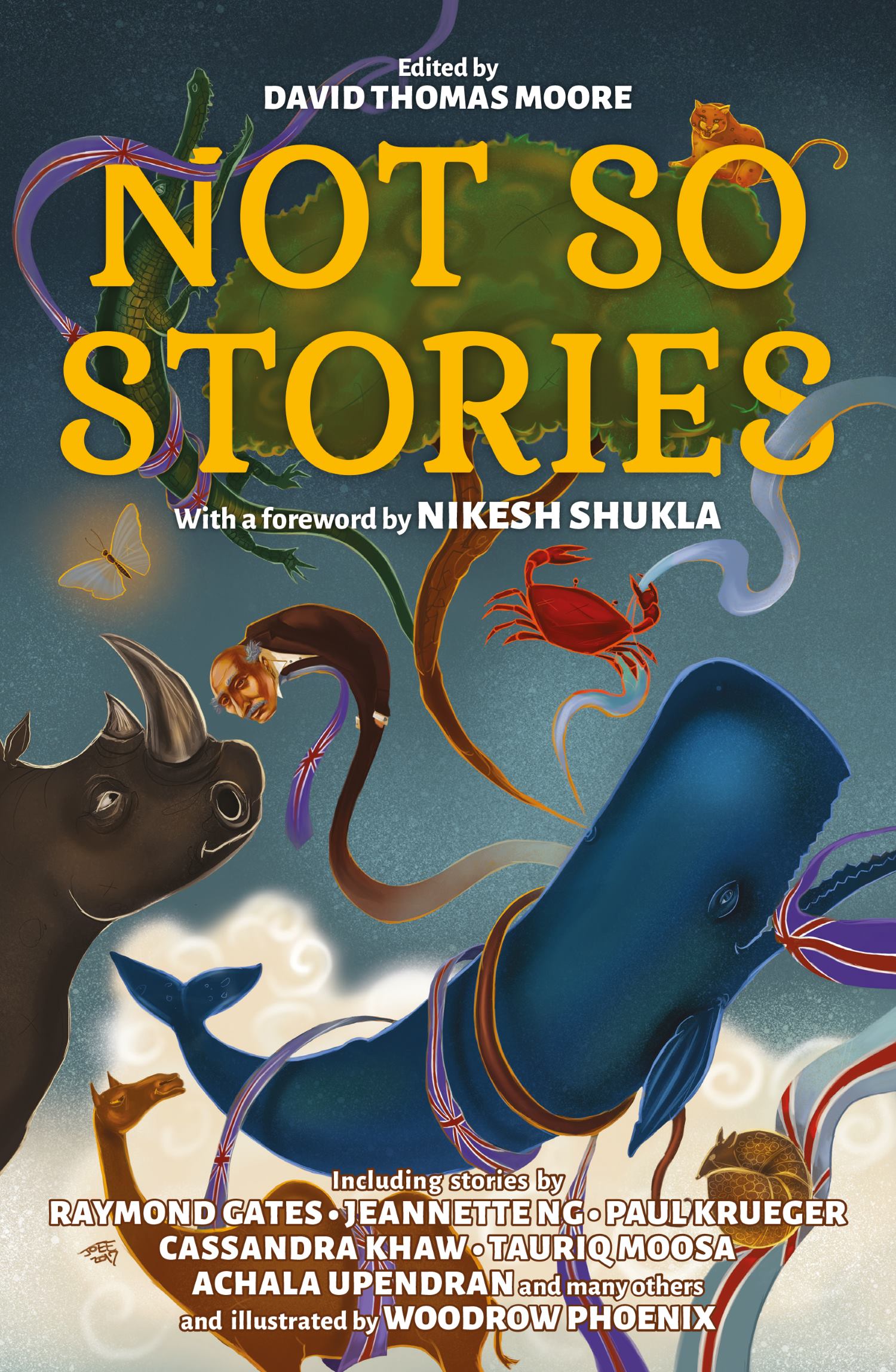

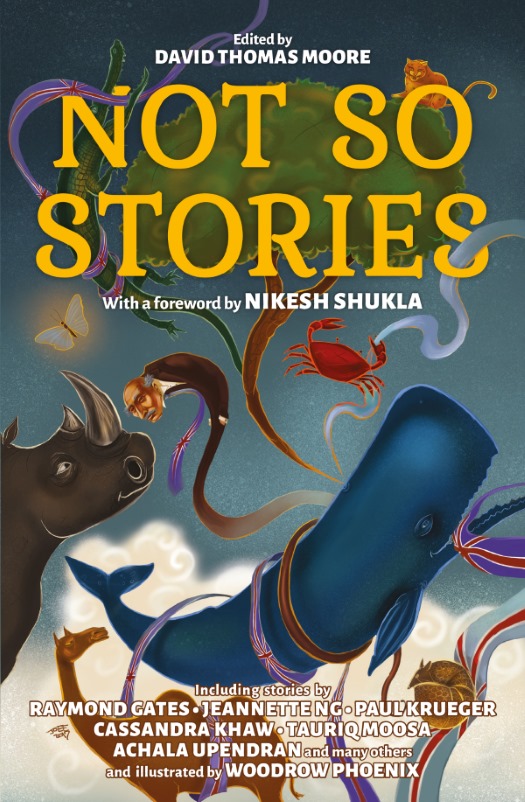

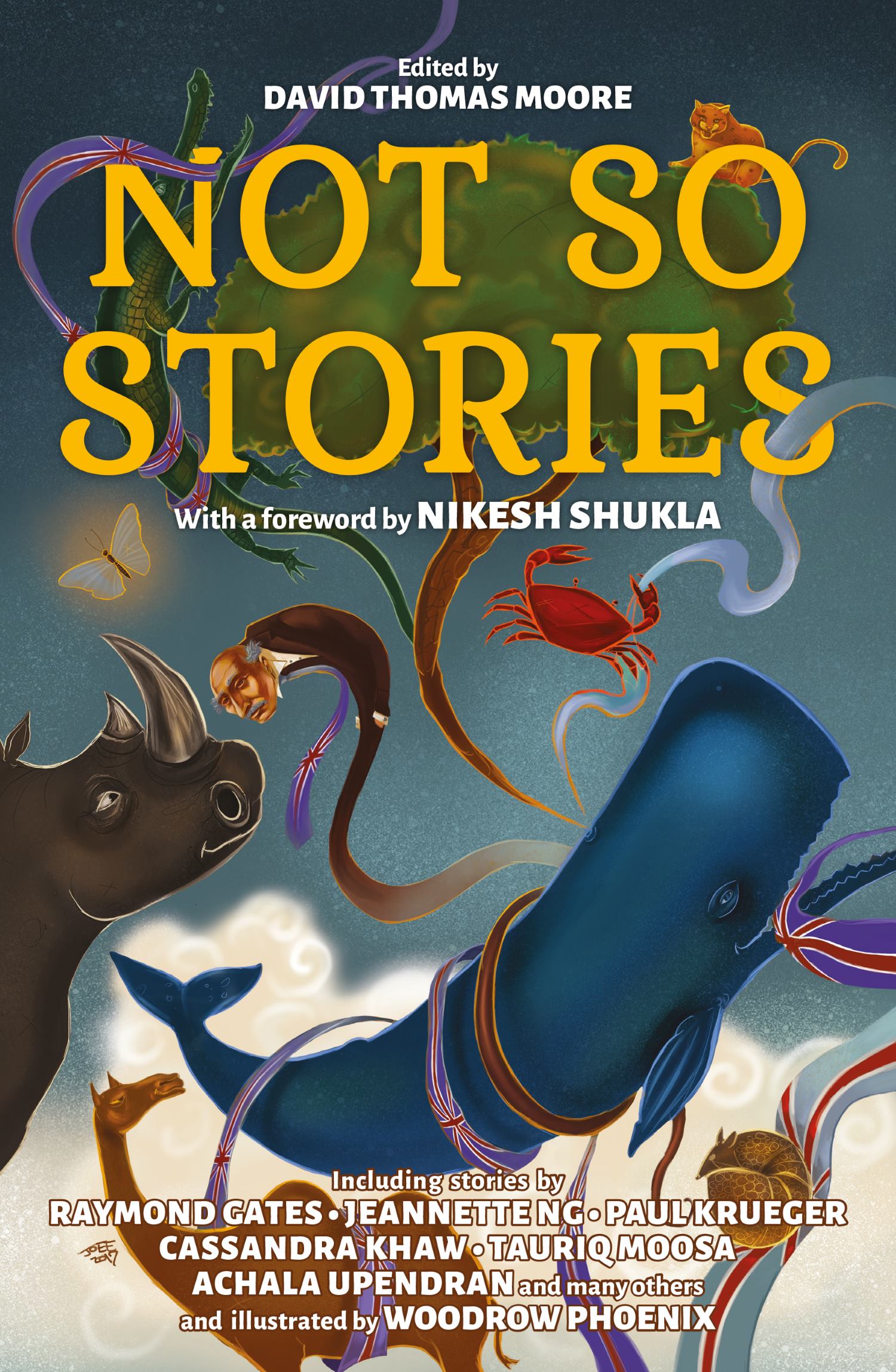

Not So Stories is available for pre-order now!

Pre-order: Amazon|Google|Kobo|RebellionStore