Early in my writing career a former friend asked me, “why can’t you write something nice for a change?” He actually meant well, but I had a hard time answering him. Finally, I mumbled something like, “I just seem to have a talent for the unpleasant.” It wasn’t a very satisfactory answer for either of us.

It’s a bit like that old question, “Why do you write horror?” Somewhat impossible to answer, especially since many of the people asking the question already assume there must be something wrong, or broken, with anyone who feels compelled to write about terrible events.

My late wife Melanie used to say, “if something upsets me, or disturbs me, I don’t want to run away from it. I want to step closer to it, poke it, and see what all the fuss is about.”

That was one of the reasons I married her. So often, when she spoke from the heart she seemed to speak for my heart as well. We both often wrote about unpleasant things, things that we might wish no longer existed in the world. And yet there they were, and we found we couldn’t just ignore them.

Not everyone wants to read about unpleasant things. They feel that there’s enough bad stuff in real life that they’d rather not encounter it in fiction. I understand that attitude, and I respect it. But that’s not why I read. And it’s not why I write.

People who have met me are often surprised by how optimistic I am. I am passionate about life. I am passionate about my children and grandchildren. I am passionate about literature and art. Even when things go badly, and if you live long enough you discover that occasionally, inevitably, sometimes things will go very badly indeed, I understand that these events are still part of that long, convoluted, and wonderful narrative that makes up a life.

The Buddhists have a word, dukkha, which is often translated as suffering, but it’s something more complex. Dukkha refers to the experience that everything is impermanent, impossible to grasp, unknowable. It’s what creates that vague feeling of anxiety and dissatisfaction that many—if not most—people feel under the surface, most of the time. It’s like that annoying song you can’t forget, which you’d do anything to escape. The Buddhists would say don’t try to escape it—embrace it. They would have us turn toward suffering, take it in and own it, and with a new sense of wholeness discover the meaning in it, and allow it to open a new path.

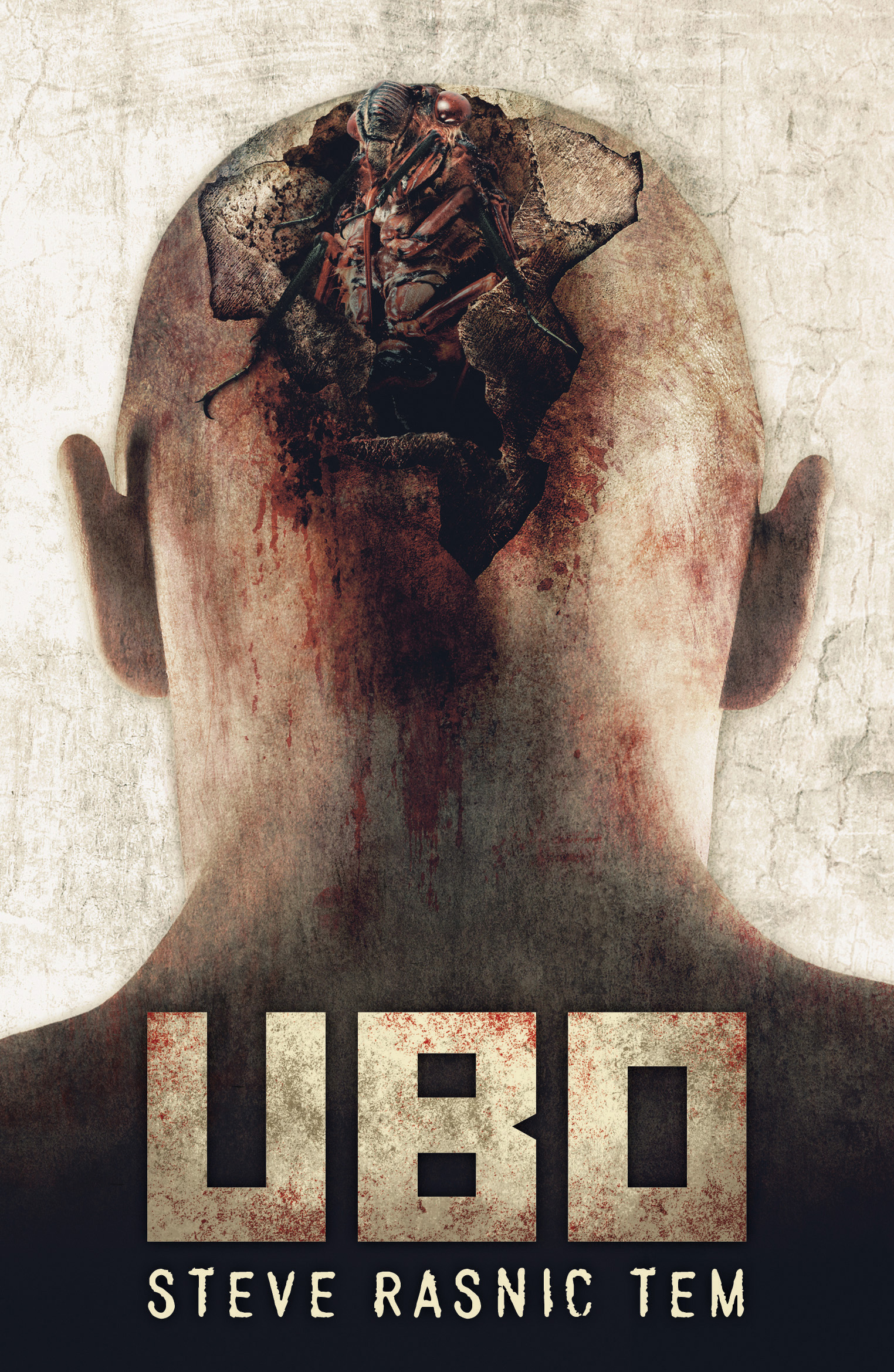

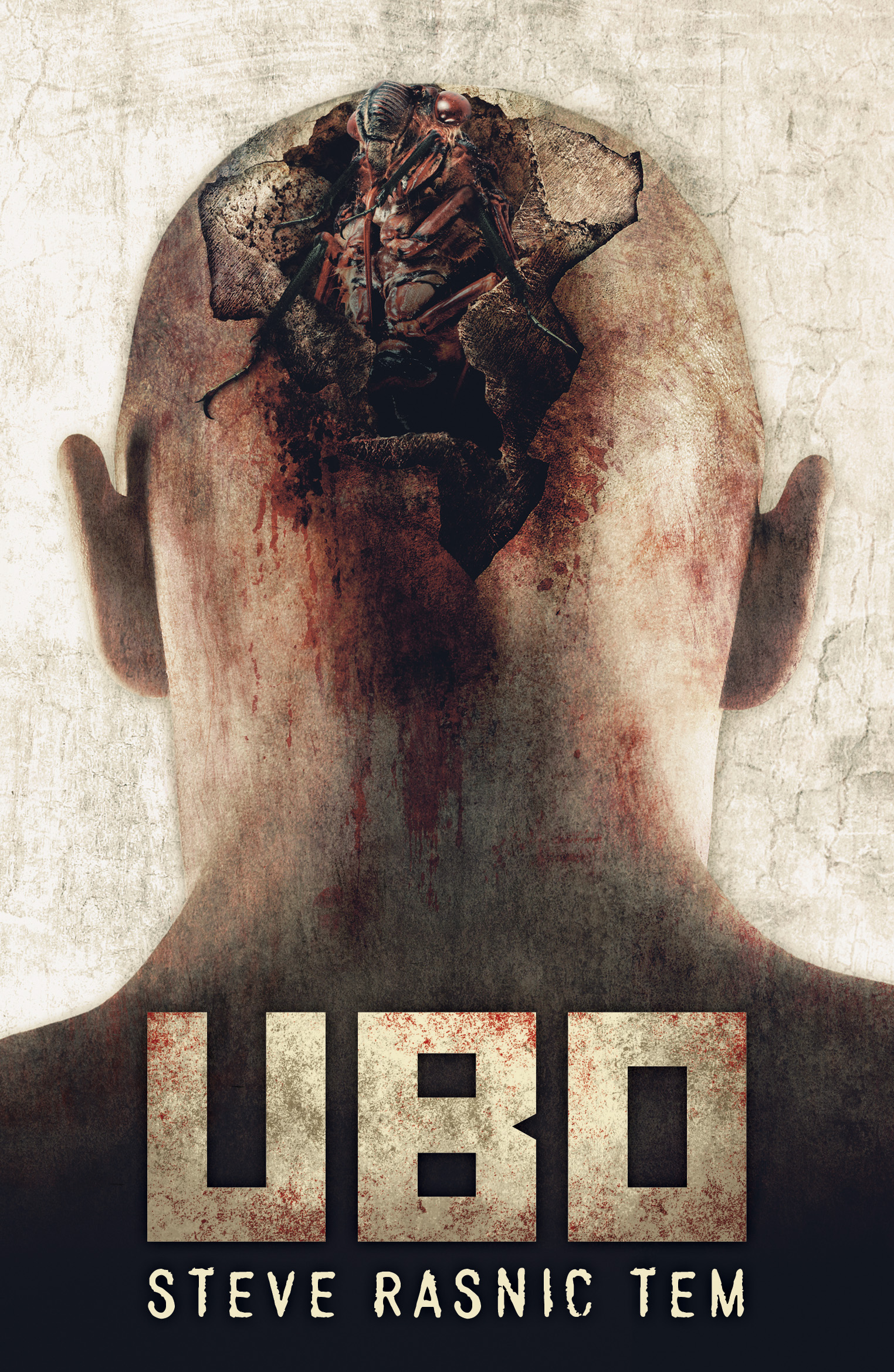

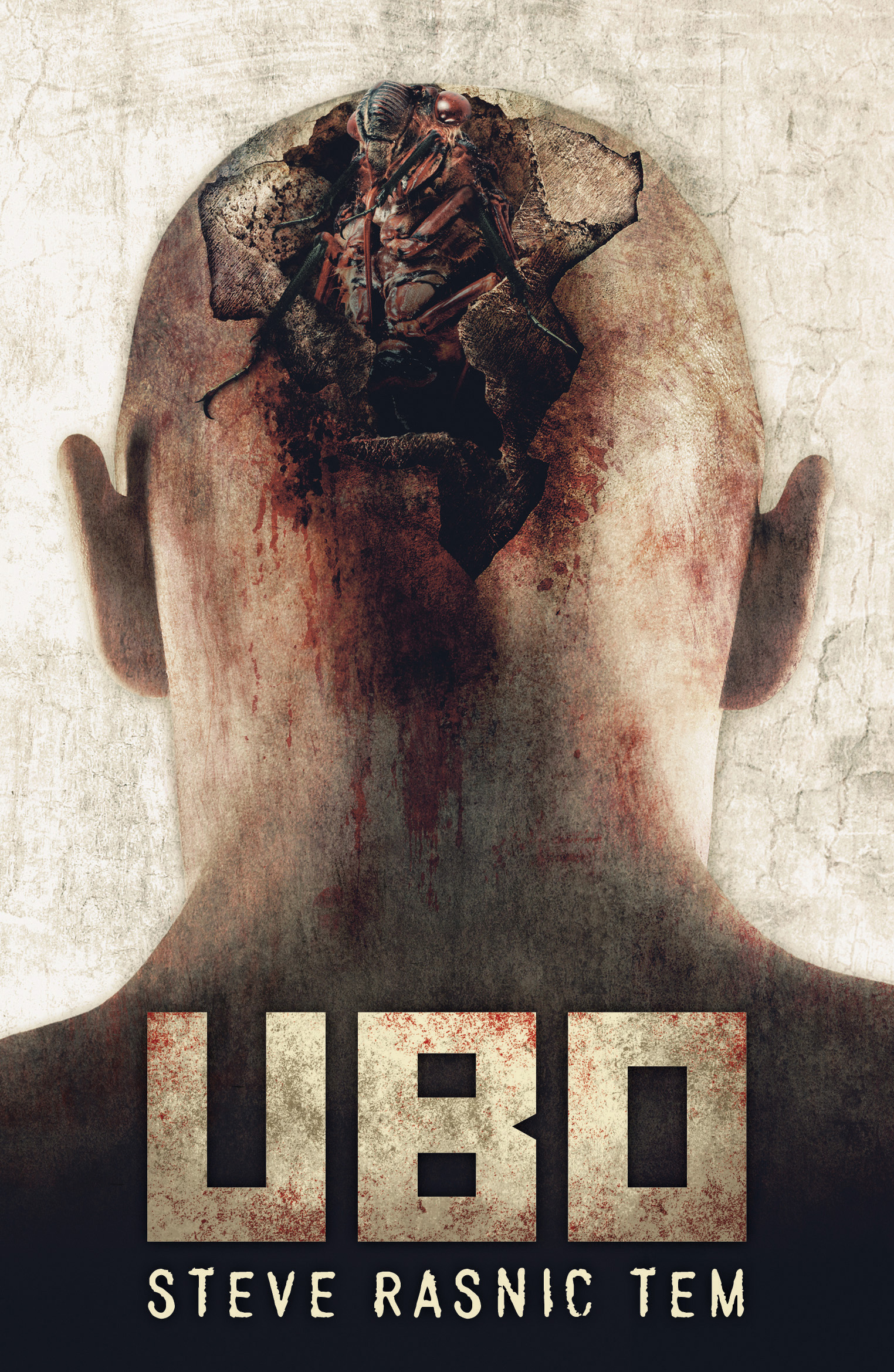

My new Solaris novel Ubo is about one of my biggest fears—violence. Violence has always appalled me, with how it destroys, how it deadens both the perpetrator and the victim, how it diminishes us all. Most of the time I’d rather pretend it’s not there, but turning my back on it doesn’t make it go away. So back in my undergraduate days (a long time ago in a land far away), I started working on this novel, designed to be a meditation on violence. It took a long time to finish in part because I had no idea how to write it. You might say that it has taken most of my career to learn how to write Ubo.

The final result is a blend of science fiction and horror exploring violence and its origins. During the course of this novel I inhabit the viewpoints of some of history’s most violent figures: Jack the Ripper, Josef Stalin, and Heinrich Himmler among others. I wanted a range of points of view through which I could examine violence. I’m not a genius—I didn’t expect to arrive at some magical solution for humanity’s propensity towards violence. At best I hoped to make people think by means of a fascinating, somewhat twisted story. For a writer of fiction that is more than sufficient.

One of the challenges of writing a story about unpleasant things is that you want readers to read all the way to the end. Completely blow them up in one chapter and they’re unlikely to want to read the next. You have to pace things properly. You have to learn how much to reveal and how much to conceal and when. You have to give them reasons to keep reading.

Melanie and I always read each other’s work before sending it out into the world. Yet I hesitated to give her Ubo because her sensitivity to violence was even greater than mine, and she had a particular aversion to writings about Nazis and the Holocaust. With immigrant Jewish grandparents that landscape formed the background of her worst childhood nightmares (and of course that content is covered in Ubo, for what would a meditation on violence be without it?). But she insisted on reading it, and we quickly realized that if I could make Ubo work for her, then that would bode well for the readership at large.

So I owe much of the final form of this novel to Melanie’s suggestions. Some chapters are very close to their initial drafts from the mid-1970s. Others have been thoroughly rewritten a dozen times or more. Nothing happens in this novel in the exact order I thought it would. It’s been quite a ride, and just one small revelation—if you find hope near the end of your journey through Ubo, it is neither delusion or accident.

My wife Melanie passed away in February of 2015. Ubo is the last work of mine she read. It was her favorite of my novels. The book is dedicated to her.

Ubo is available for preorder now

Preorder: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Google|iBooks|Kobo