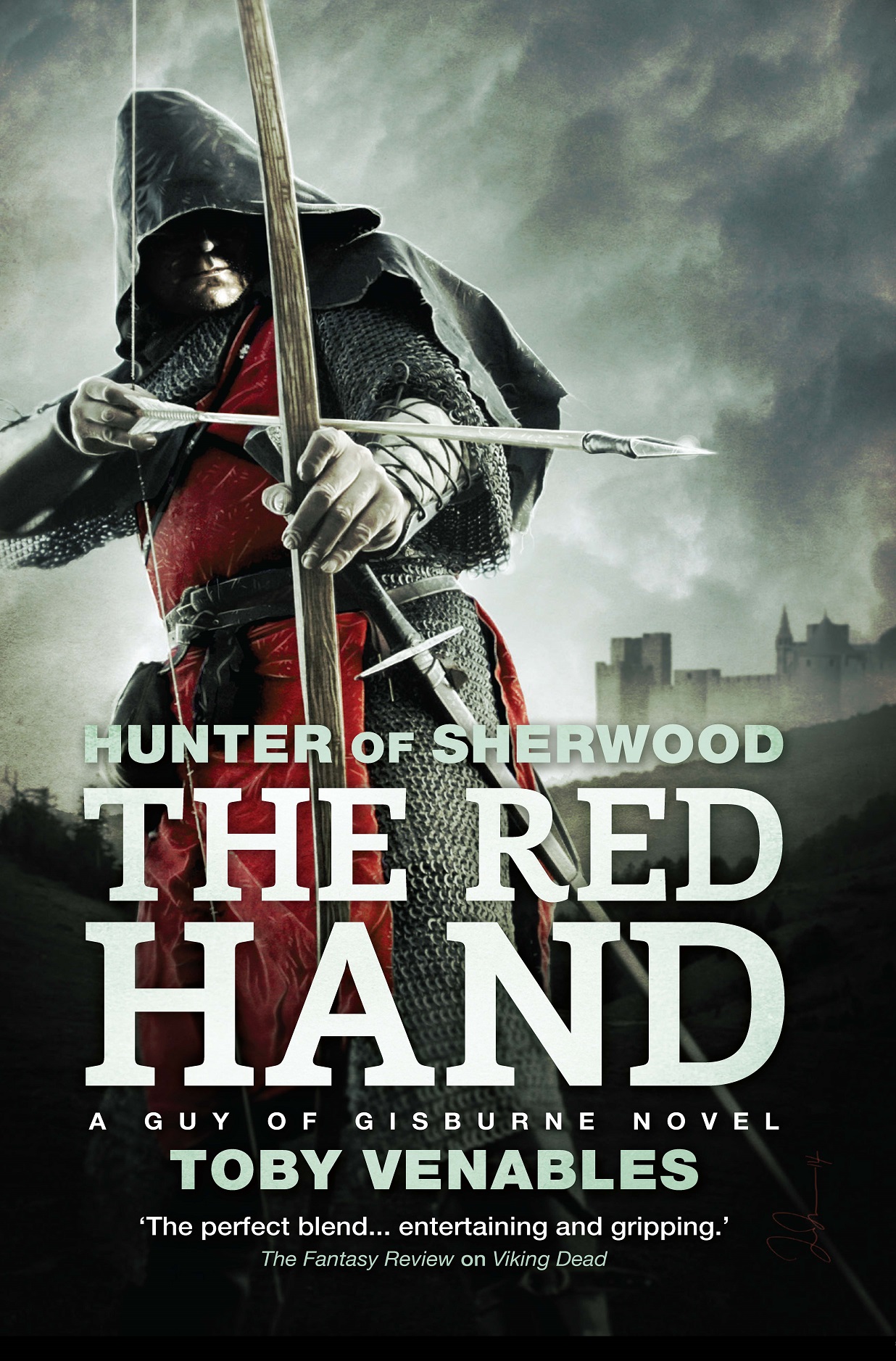

HUNTER OF SHERWOOD – THE RED HAND

by Toby Venables

Part I: THE COMING APOCALYPSE

I

Jerusalem

March, 1193

Asif al-Din ibn Salah watched the rat lope along the dark tunnel ahead of the flickering light from his torch.

It was a big rat. A fat rat. As big as the cats that darted about the alleys off the Malquisinat. Those mewling, wide-eyed creatures scavenged a fair living off the so-called ‘street of bad cooking’ – but they were puny specimens next to this hunched monster. Asif shuddered at the sight of it. For a moment it paused and waved its wet snout in the air like a dog picking up a scent. How such a thing were possible in this foul place, Asif could not guess. The mere thought of the thick stench that lapped about him – and the horrid sheen of the rat’s slimy, matted fur – made a sour wave of nausea rise from the pit of his stomach.

He shook it off. Asif needed his wits about him, down here. If the reports were to be believed, there were far worse things than rats.

Intelligence on what had been going on in the forgotten tunnels was garbled – fragmentary at best, and in its details, often bizarre. People had spoken of whole cartloads of provisions – dozens of barrels – disappearing near the sewer’s entry points, as if some huge thing had emerged from the subterranean labyrinth under cover of night and swallowed them up. One account – from a terrified Greek merchant who found himself alone one night near the Pool of Siloam – spoke of a man with the blank, expressionless face of a doll rising from under the ground. Another, of a walking statue of a dead Templar. More than once, Asif had heard the claim that the effigy of the Leper King had got up and walked, and was lurking beneath the city, ready to drag unwary Muslims into the depths. One old Jewish scholar muttered a word whose significance Asif had not fully understood, and which all flatly refused to explain to him: go-lem.

There was one common feature: Christian knights. What interest Christian knights might have in Jerusalem’s sewers was baffling. Asif – who had been resident in the city for most of his adult life, and helped to keep the peace under Christian rule before he entered the service of the Sultan – knew this city as well as anyone alive. Yet even he was perplexed. Jerusalem was a city of many mysteries – it was, Asif often joked, harder to get to know than a woman. Perhaps, after all, it was nothing. But since the city’s recapture by Salah al-Din and the hapless ‘crusade’ that followed, any Christian military presence here had to be regarded with utmost suspicion.

There was another strange fact that had revealed itself to Asif in these last few hours. He’d known, of course, that rats are ubiquitous in sewers, and when he had first descended into this forgotten netherworld, it had been immediately confirmed. He had tied his clothing tighter about him, and pressed on. But as he had progressed through the cramped tunnels, Asif had seen the quantity of rats dwindle, and for the past quarter hour at least this lone adventurer had been the only beast he had encountered. The absence troubled him. Something had driven them out. It took a lot to drive out rats.

Just one had stayed – and was reaping the benefits.

Asif did not fear rats as some did. Not even in large numbers. But he had no great desire to get closer to this single, grotesquely-swollen creature. It had been well fed of late. It also had no fear of man. Where it was now heading, and what he would find there, filled him with a sense of creeping unease.

And now it was on the move again. He heard its claws scratch on the stone ledge, saw its bald, pink tail whip from side to side. Then, as he swung his torch close to where there should have been only blank wall, a horrid shape loomed from the shadows.

A face. Half human. Less than a yard from his own.

He reeled back, almost stumbling, his free right hand going to his sword. There, in the crumbling ancient wall, was a jagged vertical fissure, and emerging from it, as if prising the stonework apart, were the skeletal fingers of a dead man. His warped skull grinned from the spreading gap, the empty pits of its eyes turned on Asif, while below, part of a leg bone thrust out of the crack as if about to take a step towards him.

Asif heard a harsh curse cut the thick air, only dimly aware that he himself had spoken. In a moment, he understood. He silently berated himself. They were bones, nothing more. Dead, dry, yellowed bones. But these bones, decades old at least – perhaps centuries – had been jammed into this crevice in such a way as to give them the semblance of life. To what end, and by whom, Asif could not guess. He stood for a moment, his heart still thumping in his chest – so hard he could hear it in the flat, eerie silence. A different kind of horror afflicted him now, spawned by his attempts to imagine what could have led to this terrible fate – how one who had once lived and loved could become so pitiful in death, abandoned and forgotten in this awful place.

The flickering light of the flambeau made the shadows about the bony form dance, creating a horrid illusion of convulsive movement. He fleetingly wondered what those long-dead eyes had once looked upon – a wife, a lover, children, perhaps. But whatever this man had been in life, he was now no more than an absurd relic.

As he stood, he felt the queasy pressure of effluent flowing past his calves, and for an instant his concentration faltered. Before entering the tunnels, in anticipation of the rising stink, Asif had stuffed his nostrils with plugs of beeswax mixed with aromatic herbs, and had been breathing through his teeth. But now – thanks, in part, to the panicked panting his skeletal friend had inspired – he was beginning to taste the foul stench. His stomach knotted, almost making him retch. He fought it down, and, by way of distraction made himself stare again into the lifeless, hollow eye-sockets of the forgotten man.

He thought of Qasim.

Qasim had never wanted to come down here. But if you were an agent of the Sultan, you went where you were told to go – even if where you were told to go was a sewer. No one relished the idea of wading through shit, no matter how fervently they believed in the mission. To Qasim, however, there was something far worse than that, something that made him even less comfortable with the whole enterprise: wading through the shit of infidels. Especially worrying to him was the prospect of having to traverse the drains beneath the Christian quarter. “It’s not just that they are godless,” he said. “They are unclean. They eat pig…”

Asif sympathised, but – somewhat to his surprise – found his own feelings on the subject to be far more pragmatic. It was crazy to think in terms of degrees of uncleanliness down here. The slurry that now lapped about his ankles was about as unclean as anything could get, and the religious persuasion of the arse it had dropped out of a detail too far removed to trouble him. But no matter how many times he said it, Qasim just shook his head, and shifted uncomfortably, as if somehow troubled that his friend did not share his view.

A week had passed since Qasim had ventured into these gloomy tunnels. There had not been sight or sound of him since.

All at once, Asif was struck by an image of poor, doomed Qasim standing on this same spot, contemplating the same long-dead visage with its mocking grin. Asif’s desperate desire to live – to get out of this place – suddenly multiplied a hundredfold.

The flame hissed and crackled on the damp, square stone ceiling of the cramped tunnel, snapping Asif out of his reverie. He turned from his grim companion and focused again on the narrow passage stretching before him, and became aware of a dark intersection ahead.

Something glinted low down in the blank gloom. Two pinpoints of reflected torchlight. He took a step forward. As his eyes adjusted, he saw that the rat had stopped, and was looking back at him, almost as if making sure he was still following. It turned, and scampered around the corner.

Asif set off after it.

He could now clearly see that this tunnel joined another, larger one just a few yards from him. This was, without doubt, the route Qasim would have taken, following the tributary into the wider drain.

From up ahead came an echoing sound of movement. His muscles tensed. Something bigger than a rat. And a dim, reflected light, shifting away to the right. People. He instinctively lowered his torch and thrust it behind him – then cursed as it momentarily cast his vast shadow onto the far wall of the adjoining tunnel. A stupid error. He flattened himself against the slimy wall, praying it had not been seen. There came no shout of alarm. No sudden, urgent movement. Slowly he edged away from the intersection, back against the uneven stones – back to the dead man with his perpetual grin.

Still no sign that he’d been discovered. Asif had been lucky. And it would appear he also, now, had the advantage; he knew they were there, but they, as yet, had no inkling he even existed. A difficult decision needed to be made. He could not risk announcing himself to them as he approached – but in order to avoid it, he would have to extinguish his torch, or leave it behind. Asif stared down at the soupy, lumpy liquid flowing about his feet – only half-aware that, in this light, it seemed to possess a strange, blue sheen – and contemplated thrusting the torch into it. It would plunge him into near total darkness. Asif hesitated – then, turning instead to his bony companion, muttered a sheepish apology, and jammed the shaft of the torch into the skull’s gaping mouth. Fire was not easy to acquire down here. He would not throw it away unless he had to. Drawing his long, straight-edged sword, he headed on again, towards the new tunnel, the glimmer of his torch dwindling behind him.

Once his eyes adjusted to the gloom, Asif was surprised at how much he could see. This tunnel had a higher, curved ceiling, constructed from surprisingly large stones. These tunnels were said to be from the time of Herod the Great – which seemed consistent with Asif’s observations of the city’s structures above ground (he had, over the years, become an obsessive student of its complex, layered architecture). The smaller tunnel he had just left, with its flat slab roof, would have been considerably older.

Sound behaved differently in this tunnel. Shufflings, splashings and strange whispers echoed weirdly along its length, sometimes accompanied by a tuneless humming. They baffled his senses, often seeming to come from behind him, from the walls themselves, or just inches from his ears. The air tasted sharp and acrid.

Then there was the light.

The reason he could see anything at all, he gradually realised, was due to the distant torch flame of his intended prey. It was now a clear glow ahead of him – flickering and moving, sometimes bright, sometimes fading, but always there. Within it – perhaps holding it – and in near constant movement, was what he assumed to be a human figure. And, from time to time, when the figure itself disappeared from view, the light threw into silhouette a huge, unidentifiable shape – uneven, but roughly conical, far taller than a man, and at least five times as wide at its base.

Asif advanced slowly, steadily, at pains to make no sound that peculiar tunnel might carry to his enemy’s ears.

The light stopped moving – was raised up so Asif could clearly see its flame, wobbled once, then hung motionless in the air.

There was a thump. The sound of some heavy wooden object being moved into place. A cough. Then the humming resumed.

As he neared – crouched, half-pressed against the left-hand wall, sword ready in his right hand – the hum began to resolve into a tune. A Christian tune. The torch, he now saw, had been stuck in a crack in the wall. The silhouette that had placed it there now had its hands free, and was lifting what looked like a small barrel. Humming quietly to itself, it heaved the cask into place upon a great heap of similar vessels. It was heavy; full. But of what?

Asif was now yards away, moving with painful deliberation, barely breathing. Suddenly the figure turned to face him. Asif froze, praying that he was still undetected in the shadows. The figure strode purposefully towards him. Asif raised his sword, ready to strike. It turned again, and headed to the far side of the heap of barrels, oblivious to his presence, still humming its tune.

Asif simply stood for moment, barely able to believe he had not been discovered. The figure had been a man. For a split second, he had seen him clearly. Lean, European, with a neatly clipped, coppery beard. Beneath his dark cloak was the glint of mail, at his belt a fine sword. A Christian knight.

The sound of his movement receded, and Asif crept towards the great pile of barrels. If he could just identify their contents before the knight returned, it may perhaps reveal his purpose. If not, his goal would be to follow the knight – and try to capture him alive. He hurried the last few yards to the barrels. He risked being heard, but his greater concern now was being seen. He had entered the pool of light spread by the torch upon the tunnel wall.

Reaching for the nearest barrel, he pulled at the wooden bung. It was stuck fast. He tried the one next to it. The same. Then one above. It shifted, and gave. He rocked the barrel, and some of the liquid within slopped out. It was somewhat viscous. Also dark – at least, in this light – but its appearance alone told him little. It struck him, then, that he was currently denied the one sense he most needed – the sense of smell.

Asif was about to remedy this situation when another, far more alarming fact impressed itself upon him. He could no longer hear the knight.

His blood ran cold. He turned. The knight stood glaring at him, eyes reflecting the flame of the torch, filled with a wild hatred.

The knight lunged, grabbing his tunic, teeth clenched, his breath on Asif’s face. Both stumbled. The knight let go with one hand, and Asif staggered backwards. His adversary was too close for him to deliver an effective blow with his blade – and suddenly Asif saw a knife flash in the man’s fist. With all the force he could muster, he smashed the pommel of his sword down like a hammer upon the knight’s temple. The man dropped like a stone, face down in the muck – and did not move.

Asif prodded him with his foot, and turned him onto his back. No response. He appeared not to be breathing. Asif gave thanks to Allah for sparing his life – then kicked the knight in frustration. Why, when you needed someone dead, did it take twenty blows to get the better of them – then, when you needed them alive, they immediately gave up the ghost with one knock to the head? Whatever secrets this man might have divulged were now lost forever.

A glimmer of light on the wall opposite the barrels suddenly caught Asif’s eye. The dark, rectangular shape that he had thought was merely shadow was glowing feebly. Flickering. It was the entrance to another, smaller tunnel – and, deep within it, someone was advancing towards him. At some indefinable distance, two points of light bobbed into view, like eyes in the dark. Distant torches.

For Asif, it meant a second chance. But this time, there would be two of them.

He backed into the shadows to the side of the barrel heap, and waited.

II

Galfrid regarded the warm, pungent sludge flowing about his calves and tried not to gag. “‘Come to Jerusalem,’ you said. ‘Good wine. Good food. Lovely climate. Walk in the footsteps of Christ…’” He poked at something lumpy with his pilgrim staff and, with a grimace, decided against further investigation. “Obviously I missed the passage in the scriptures where Jesus went down the sewer…”

The figure advancing ahead of him said nothing. For a moment the taller man stopped, moving his torch to the left and right, his attention focused on the change in the size of the slabs that formed the ceiling of the tunnel. Then, without a word, he moved on.

Galfrid knew they must look an unlikely pair: he, dressed as a Christian pilgrim complete with staff, pilgrim badges and hooded cloak; his master outlandishly clad in the manner of a minstrel or joglar. Nothing could have been less appropriate to his master’s temperament. The incongruity had caused Galfrid much hilarity, even in these grim surroundings. But incongruity was the nature of disguise – and disguise had been necessary.

As they walked, Galfrid’s gaze came to rest on the long, narrow wooden box slung across his master’s back. He chuckled again, and shook his head. It was perhaps just long enough and wide enough to contain two dozen arrows, but he knew it contained nothing of the kind. From one end protruded a curved handle delicately wrought in iron, and along its body was an even row of wooden keys that rattled when the box was bumped. Galfrid reflected on his master’s dogged insistence on bringing it down here, and wondered if he was the first man ever to have introduced a hurdy gurdy into a public sewer.

“It’s just…” continued Galfrid wistfully, as if his master had deigned to respond, “I thought we might have a chance to actually enjoy some of those things. You know, see the sights. The Holy Sepulchre, maybe…” He’d tried to sound casual with his example, even though it was perhaps the fifth time he’d mentioned it. Galfrid didn’t know why he was bothering – his sad obsession with churches and cathedrals was well known to his master. He looked down again, and immediately recoiled. A dead rat had bobbed to the surface. He felt it bump against his leg and continue on its way. He was coping with the smell – just – but somehow the sight of that was threatening to shatter his resolve.

Galfrid belched, and felt a sudden, urgent need to put thoughts of good food and wine out of his mind. “Is this what they call ‘going through the motions’?” he said.

Guy of Gisburne had grown so used to the complaints of his grizzled squire that now the comments barely registered. But he also had other, more immediate things on his mind. One wrong turn in these tunnels, and they may never find their way out. Even supposing they kept track of their progress; if they ventured too far to make the return before their torches died… Well, that would be a fresh kind of Hell. And then there was their adversary. He was down here, somewhere. Amongst the rats and the stinking waste. Gisburne was sure of it. But to what purpose?

He heard Galfrid huff again and decided he would benefit from some attention.

“Relax,” he said, cheerfully. “Try to enjoy yourself. You’ve already got further than the Lionheart did.”

“Had King Richard succeeded in taking Jerusalem,” said Galfrid, no longer bothering to disguise the disgust in his voice, “I somehow doubt that a visit to the sewers would have been his first priority.”

“Unless he read that bit of the scriptures you missed,” said Gisburne. It showed, at the very least, that he had been listening.

Galfrid gave a snort and muttered under his breath. “At least Christ could’ve walked on it rather than in it.”

There was one key reason put forward to explain why the Lionheart’s conquest of Jerusalem had failed. It was said he had been troubled by reports of growing chaos in his kingdom – of open rebellion by his envious brother John, who wished to take the crown from him. And so, just days from capturing the Holy City – his one avowed object on this crusade – he had turned back towards England. It was an attractive story – and one Gisburne knew, with every fibre of his being, to be false. He knew it because Richard cared nothing for England, and never had. He cared only for battle, for conquest, and for the prizes that came with them. If he could defeat Salah al-Din and return Jerusalem to Christian hands, he would be acknowledged as the greatest warrior in the world – and if he could make himself king of that holy realm, well, all the better. Richard had no interest in sitting on a throne, but every interest in winning it.

Gisburne felt he knew the real reason the Lionheart had turned from Jerusalem: he was afraid he would fail. In Salah al-Din, he had at last encountered a general who was his equal. For the first time in his life, he had been forced to contemplate the possibility of defeat, and all that this entailed. No stronghold had ever been able to withstand his assault. He had cracked every city, every castle that stood against him. But if he were finally to be broken upon Jerusalem’s walls, at the hour of Christendom’s greatest need, and with the eyes of the world upon him, well… Where would his reputation be then?

So he had not even tried. Somehow, in doing so, he had also made retreat look like concern for his own beloved kingdom. If anyone had a charmed life – an inexhaustible well of good luck – it was surely Richard. At least, so Gisburne had thought until three days ago. Then, from one of the contacts he still had in the city, he learned that Salah al-Din – also doubting his abilities against a formidable opponent – had been one day away from abandoning the city to the surrounding Christian forces. Had Richard only known to wait for one more sunrise, Jerusalem would have been his.

“So,” said Galfrid, “how long do you propose we wade about in this garden of earthly delights?” Down here, it became hard to judge the passage of time. The moments seemed painfully long, and they had now been pacing these tunnels for at least an hour – picking their way slowly, carefully. In all that time they had found nothing of note beyond a few ancient bones – both human and animal – some broken barrels, a large quantity of rats – which, happily, dwindled in number as they proceeded – and, most bizarrely, a six-foot brass trumpet with a leather slipper stuffed in the end.

“We go where the trail leads,” said Gisburne, without looking back. “Until we find what we’re looking for.”

Gisburne was well aware that this was primarily his mission and not that of their master Prince John. John had indulged him, nonetheless. In the months leading up to Christmas, there had been another, far more pressing problem, closer to home – a problem that had occupied Gisburne’s thoughts utterly. But always, at the back of his mind, he had this other, more personal duty waiting its turn. It was a duty not to a prince, but to a humble squire. To a friend. To Galfrid.

Then, on Christmas Eve, the great problem had been swept aside with startling finality. It had not been without cost. But it had at least left Gisburne free to pursue other aims – even with a void to fill – and he had turned back to this piece of unfinished business with renewed vigour. John, exhilarated by their recent victory, gave his full blessing to the enterprise, and put all available resources at Gisburne’s disposal.

It had taken them eight months of dogged investigation to get to this point. Eight months of false leads, blind alleys and disappeared informants. Their adversary was subtle, and at the start, their own methods had been crude. Time and again, as they drew close, their prey would go to ground – vanishing without trace, like a phantom. There were those who believed he was literally that – that he had perished that time in Boulogne, over a year before, and that what now walked the earth was some kind of vengeful spirit. Gisburne had never paid heed to ghost stories. In his experience, the dead stayed dead. But this one was fiendishly clever. And so they had learned, and adapted. With a restraint that had tested their resolve to the limit, they had finally succeeded in keeping themselves invisible to their adversary, resisting opportunities to strike where victory could not be assured, waiting instead for him to reveal his grand plan.

Such restraint did not come easily. Gisburne was a man more used to the battlefield than the chessboard – to attacking hard, or bypassing the fight altogether, when it was to no purpose. During these days, as so often, Gisburne had held fast to the words of his old mentor, Gilbert de Gaillon: “The object of a hunt is simple. Not to attack the beast, but to kill it. You must therefore ask yourself, will attacking now achieve this end – or push it further from your grasp?”

Now, they were tantalisingly close. To what, neither yet knew for sure, but both sensed that the day of discovery – a day they had worked towards with steady determination – was finally upon them. And both were now certain, beyond any doubt, that the one they sought was here, at the heart of this labyrinth. To finally ensnare him – to have him removed forever from the earth… Well, Gisburne knew that, for all his griping and complaining, Galfrid would walk slowly over hot coals in Hell rather than pass up that opportunity.

Gisburne paused and looked about him. “This tunnel joins a larger one up ahead. If I have it right, the Via Dolorosa is now somewhere above us.” He turned to Galfrid. “So, in a way, you are walking in the footsteps of Christ. Just… a couple of dozen yards lower.”

Galfrid gave a grunt of irritation and passed a hand across the stubble on his head. He had thought, before they ventured down here, that it would at least be cool in the tunnels. In fact, it was sweltering. His head throbbed, the stench seeming to lap against it on every side.

Gisburne moved off again – then stopped so suddenly that Galfrid went into the back of him. Just ahead, projecting a few inches above the surface of the effluent at a point in the tunnel wall where, it appeared, another tunnel entrance had been blocked up, was a rough, horizontal slab of stone. On the slab was the body of a man.

His throat was cut, the wide gash in the parted, grey flesh grinning open like a lipless mouth. But while the flesh about his neck remained otherwise intact, his face, left arm and left leg had been eaten to the bone. Whatever rats remained hereabouts had evidently made use of him. A sweet, sickly odour rose from what was left.

“Who is he?” said Galfrid in a whisper. “And what in God’s name brought him down here?”

“It was more likely in Allah’s name,” said Gisburne. He crouched over the grim corpse. Fine scale armour glinted upon his torso. From his belt hung an empty sword scabbard and a sheathed knife, both with fittings of gold. “Arab. Well dressed. Well armoured. One of Saladin’s. The elite. Whatever it was brought him down here, it certainly wasn’t need.” He had occasionally heard of beggars and lepers taking refuge with the dead in catacombs, but this man was clearly neither.

“The body hasn’t been plundered,” observed Galfrid. “Not by humans, at least.”

Gisburne glanced again at the exposed skull and suppressed a shudder. “So, whoever killed him…”

“…was not a thief. And also not in need.”

Gisburne stood. “I suspect his reasons for being down here may be the same as ours. And that he found what – or who – he was looking for. To his cost.”

“Poor bastard,” said Galfrid.

Gisburne stared off into the gloom ahead. For a moment, he thought he could detect a faint glow at the edge of his vision – but the effect disappeared as his eyes tried to focus on it.

“The body is only a few days old,” he said. “It means we’re close.”

They followed the flow towards the intersection with the wider tunnel – and within minutes Gisburne understood that his fleeting impression had been correct. Ahead, framed by the distant tunnel’s mouth, was the flickering orange light of another flame. It was stationary. As they neared, he could see the pool of light that spread about it, within which was a large, uneven dark shape. Objects of some kind, stacked in a pile. But there was no movement of any kind. No sign of life.

Gisburne drew his sword, and quickened his pace.

They stopped at the edge of the larger tunnel, its ceiling arcing above them, and stared across at the dark, shadowy heap.

“Barrels,” said Gisburne.

“Barrels,” repeated Galfrid with a nod. “And there was me thinking it was going to be about the trumpet. So, are we too early, or too late?”

The torch upon the opposite wall had been burning no longer than their own. Someone had been here, and could not be far. But which way? Gisburne turned his own torch first to the right, then to the left. “This flows south-east, ultimately to the Kidron Valley. The tunnel we have just travelled comes from the Christian quarter. Across there are tributaries from the Muslim sectors, with the Jewish area up that way.”

“Christian, Muslim, heathen or Jew,” said Galfrid, his nose wrinkling, “shit still smells like shit.”

“Except…” said Gisburne, a frown creasing his brow. “When it doesn’t.” He sniffed the air. “Do you smell that?”

“Are you joking?” said Galfrid. But beneath the dank, hot reek of stale urine and fermenting excrement, another, sharper smell was rising. Something half familiar.

Galfrid sniffed tentatively. “Vinegar?” he said. At Gisburne’s suggestion they had doused their skin with the stuff before coming down here. By this method, Gisburne’s old comrade Will Pickle had fended off dysentery throughout William the Good’s entire battle campaign against the Byzantines, earning his nickname in the process. He had been convinced its strong, clean smell kept disease-laden odours at bay. Gisburne could think of no better occasion to put that to the test.

He stepped out into the tunnel and stopped, flame held at arm’s length, his narrowed eyes scanning the uneven stonework of the clammy ceiling, then every crack and fissure in the crumbling walls. Nothing. Tentatively, he lowered his torch towards the black surface of the lapping effluvium.

Upon it, he now saw, was a curious, iridescent sheen.

Galfrid frowned and stooped to examine the fluid, moving his own flame closer as he did so. Gisburne grabbed the torch. “I suggest we keep our torches above waist height,” he said. “Petroleum. Everywhere about us. If that should ignite…”

Galfrid stared, wide-eyed. “…we’ll be roasted alive.” He raised his torch slowly above his head.

“No rats,” said Gisburne in sudden realisation. “That’s why there are no rats. But where’s it coming from? And why is it here?”

“The barrels?”

Gisburne turned his torch flame upon them. A few had been unstoppered or broken open, but they appeared mostly intact. “There must be more,” he said. “Many more. It’s covering the whole surface.” He looked away to their right, into the deep dark of the arched stone passage. “And it’s flowing from… that direction.”

He started off into the gloom, but no sooner had they passed the heap of barrels than Gisburne felt Galfrid grip his arm. He turned and immediately saw what had caught the squire’s attention. By the left wall, almost obscured by shadow in the cleft between the barrel heap and the stonework and partially submerged, was another body. This time it was clearly fresh, and no Arab.

Gisburne waded over towards it, and was just crouching over the dead man when he became aware of a movement in the deep shadows barely a yard from him. Too late.

The man was on him in an instant. In desperation, Gisburne brought his weapon up. He was aware of a flash of steel – the glint of scale armour, golden in the torchlight. The other’s dark face loomed as the attacker swung his sword high – and stopped dead.

For a moment, both stood, transfixed. “Gisburne?” The voice was deep, seeming to echo the length of the tunnel.

Gisburne stared, eyes widening. “Asif?”

Asif – almost a head taller than Gisburne, who was tall himself – threw his big arms around his friend and clapped him on the back heartily, his deep laugh reverberating through Gisburne’s chest. Gisburne, stunned, fought to maintain his grip on his torch.

“You two know each other?” said Galfrid, incredulous. He looked around, as if reminding himself of their circumstances. “Well what are the odds? Just when I thought the day couldn’t get any stranger…”

Asif released Gisburne from his grip and stood back, his hands still on his friend’s shoulders.

Gisburne allowed himself a laugh, though the blood was still pumping hard in his veins. “Asif helped keep the peace when I was here… What? Five years ago?”

“Six!” laughed Asif.

“He was also a fabulous archer and a terrible backgammon player. Taught me everything I know.”

Asif sighed. “That was before Hattin. Before the crusade.”

“Before everything,” added Gisburne.

“Time flies when you’re having fun,” said Asif. And another big laugh welled up in him.

“Looks like you’re still in much the same game,” said Gisburne. “But in the pay of the Sultan himself, this time, unless I’m mistaken.”

Asif cocked his head. “I couldn’t possibly say.” He looked Gisburne up and down, a bemused frown pressing deep creases into his brow. “But what of you? Are you some kind of… musician now?”

If pressed, Gisburne could play two tunes on the hurdy gurdy – one of them badly. “I couldn’t possibly say,” he said with a smile.

Asif held his gaze in silence for a moment, then smiled. “Well, I think we understand each other.”

Galfrid cleared his throat, pointedly.

“Oh – this is Galfrid,” said Gisburne.

“Sir Galfrid,” said Asif, with a bow of his head.

“My squire,” added Gisburne.

“But you may call me Sir Galfrid if you wish,” said Galfrid with a broad grin. “It has a certain ring to it.”

Gisburne turned and nodded towards the body of the dead knight. “Your work?”

Asif looked irritated. “I meant only to stun him. To find out from him what all this is about. But these Europeans from their wet countries – they die too easily.” He seemed to remember who he was talking to. “No offence.”

“None taken,” said Gisburne. He crouched over the body and began to pull back the surcoat, mail and gambeson to reveal part of the man’s neck and shoulder. There, over his collar bone, was a tattoo of a skull.

“The Knights of the Apocalypse,” said Galfrid, his voice a flat monotone. “We were right…”

This was the final confirmation – the culmination of their months of toil. It would end tonight, here, within this grim labyrinth.

“I have never heard of this order,” said Asif.

“They are a recent phenomenon,” said Gisburne. “Their ethos insane, their leader a madman. Up above they went dressed as simple pilgrims. Down here, we see them for what they really are – crusaders. Though even that term dignifies their aims. Since King Richard and Saladin reached an accord, there has been peace. But the actions of these men could spark another war – a war that neither side wants.”

“Is this what they seek?” asked Asif. “An end to the truce?”

“An end to everything,” said Gisburne. “And they must be stopped. At any cost.”

“Then we have the same goal,” said Asif. “But what are those actions?” He looked at the barrel heap. “What is it they are doing down here? It makes no sense.”

Gisburne stared back into the gloom of the tunnel. “This will take us to the answer,” he said.

III

They moved on together, following the course of the large, central drain – which, Asif informed them, ran the full length of the city, passing directly under its heart. As they advanced, the smell of petroleum grew ever stronger, patches of the stuff on the surface of the city’s waste making it ever more slick and viscous. In two side tunnels they had been able to discern the now familiar dark shapes of further piles of barrels. It seemed prudent to assume there were other heaps hidden in these depths, all placed according to some dark strategy. But even they could not be the primary source of the outflow.

Just past the second such tunnel, Asif suddenly raised his hand. All stopped, and stood motionless. It took a moment for the sound to reach Gisburne’s ears – distant, echoing, steady and rhythmic. It was half-familiar, but he could not place it, blurred by the distance and the weird qualities of the honeycomb of passages. He could not even be certain from which direction it came. He glanced at the others, then moved off again.

The sound grew in volume as they advanced, its steady rhythm pounding in their ears, beating against Gisburne’s nerves. He knew now what it reminded him of, though it made no sense, not in these depths. It was the sound of a tree being felled. And beneath it, now, another sound. A meandering drone that rose and fell. Wordless sounds – but clearly a voice.

Up ahead, to one side of the main drain, they saw dimly flickering light – an entrance to another tunnel, from whose mouth the sounds echoed. But this was no mere tributary. As they neared, they saw it was another large drain at an angle to the first – not constructed in stone or brick, but hewn through the rock. “This could not be of later date than the time of King David,” whispered Asif, “and was perhaps much older even than that.” A little way along its course, it connected with what appeared to be a natural cave, on the left side of which ran an uneven ledge, almost wide enough, in parts, for two men to walk abreast. They climbed onto it, relieved to be relinquishing contact with the city’s stinking discharge.

The curving, rocky passage extended a short distance to another opening, where it appeared to broaden out into an even bigger space – the source of the light, and also of the sounds.

No longer speaking, they exchanged looks, smothered their torches and were plunged into gloom.

They listened to the steady, rhythmic sound in the dark as their eyes adjusted. The glow returned. Faces again became visible. The path once more revealed itself. Then, slowly, they crept forward towards the light.

When finally they peered beyond the mouth of the passage, their jaws dropped at what they saw.

A huge chamber opened up before them – part Roman vault, part cave, walls and ledges of ageless rock merging with soaring, interweaving arches of brick and stone, like the great crypt of some profane cathedral. All around the margins of the chamber, torches were fixed, their flickering yellow flames reflecting weirdly on the vast lake of effluent that the walls encircled. Its undulating surface – slick with an oily sheen – seemed to give back every colour but those which could be deemed natural, the sick stink of it now so heavy with petroleum as to be almost overwhelming.

And there, at the centre of it all, the all-dominating feature that elevated the scene to the status of a nightmare. From the hellish, rainbow-hued sea of ordure, reaching almost to the chamber’s roof: a ragged, teetering pyramid of barrels. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of them – Gisburne could not even begin to reckon their number. And within this, a single point of movement – a speck of dogged human purpose. Half way up, perched like an insect on a mound, a knight was breaking open a glugging barrel whilst singing a crusader hymn, each stroke of his axe in time with the music.

Huddled in shadow at the edge of this outlandish scene, the three companions gazed upon the man-made mountain with speechless incredulity. Gisburne had been trained to divine his enemies’ motives and capabilities – had thought he alone grasped the extremes to which this one was prepared to go. But nothing had prepared him for this. The mere scale of it baffled comprehension. The effort must have taken months. Simply for the transport of the barrels to have been kept secret, they must have come from dozens of locations. To have been hidden, smuggled, disguised – their contents obscured and mislabelled at every step. It seemed the work of madmen. But its execution was not mad. It was steady. Calculated. Purposeful.

Yet, even as he looked upon it, that purpose utterly eluded him. He could not inhabit the unfathomable minds of his adversaries – could not follow the warped logic that had, over weeks and months, resolutely piled up this catastrophic potential. If all this were to ignite… Gisburne had seen up close what fire could do to stone, how it had been used to break castle walls and crack their towers apart. He had made use of it himself. The piles of barrels were positioned in every part of the labyrinth, and there was no part of the city under which these channels did not run.

The Knights of the Apocalypse meant to destroy Jerusalem.

Petroleum would be released into the sewer from this vast pile, and the smaller heaps set to seep their contents into their respective tunnels. The flames would spread down the main drains and into each of their tributaries, turning them to rivers of flame. The intact barrels in each pile would catch and burn, finally breaking open to fuel the inferno. The ancient stones above would split in the heat. A horde of flaming rats would spew into the streets, setting everything afire. The walls of the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock, the Temple Mount – all would crack asunder, the whole of David’s Holy City collapsing into the pit of its own flaming ordure.

Jerusalem would become a Hell on earth.

One glance at Asif and Galfrid told him that they had reached the same conclusion. Gisburne turned his attention back to the toiling knight. “We must stop him,” he hissed.

“But how?” whispered Asif. The same question was written on Galfrid’s face. The knight’s exposed position on the mountain of barrels presented a seemingly insoluble problem: how could they get to him before he had the opportunity to cry out and raise the alarm?

Gisburne slung the hurdy gurdy off his back.

“You’re going to play him a tune?” breathed a baffled Galfrid.

As his companions watched, Gisburne slid open one end, and from within it pulled out a long, flat drawer into which several parts of some device were neatly set: a steel bow; a slender, steel-reinforced stock; half a dozen tiny crossbow bolts, some shaped like grapples; a length of cord upon a free-spinning reel. Gisburne freed the bow, snapped it into place on the end of the stock, pushed forward a steel lever and – with all his strength – pulled it back to draw the thick string. He plucked up a barbed bolt – but before placing it upon the tiny crossbow, tied the free end of the cord to a loop on its nocked end. Then he checked there were no obstructions to the cord’s free movement, and took aim.

It was not quite the purpose for which the bow had been intended. It had been meant for scaling heights – a development of its maker’s earlier experiments. In the event, once here, they had found themselves descending into the depths. There had been no chance to test its accuracy in horizontal flight; Gisburne hoped to God it would serve. There would be only one chance – and even if it found its mark, they would have to move fast.

He held his breath for a moment, then released it slowly as his finger squeezed the trigger. The crossbow leapt in his hands. The bolt flew, the cord whipping after it. The knight gave a stifled cry, crumpled, and slithered part way down the heap.

“He’s still alive!” said Asif.

“That’s the idea,” said Gisburne, and hauled on the cord. It pulled taut, springing up out of the effluent with a spray of stinking liquid. The man gave a hoarse yelp as it yanked the barb in his shoulder, slipped several feet, stopped, then lost his grip completely and tumbled into the greasy muck.

With slow deliberation, Gisburne began to reel him in like a fish.

It was painfully slow – Gisburne did not want to lose him – but the length of time he was beneath the surface of that putrid lake was surely far longer than any could survive. As they pulled him close, he seemed gone. For a moment, all stood in silence. Then a brown, slimy arm shot out of the ordure and grabbed Galfrid’s ankle. The squire staggered, was almost dragged in. Asif gripped the arm, lifted the flailing, dripping figure out of the lake in one seemingly effortless movement, and head-butted him into silence.

The knight slumped flat on the ledge, apparently lifeless – then came to in a fit of coughing and retching. Gisburne dragged him further into the chamber, beneath the light of a torch, put a knee on his right arm and leaned over him. “So, shall we keep you, or throw you back?”

The knight blinked back at him, his face contorting into a sneer. “I do not fear pain or death,” he rasped.

“I don’t need you to fear pain,” said Gisburne. “Just to feel it.” And he gave the bolt a slow twist. The knight howled in agony.

“The others – they will hear…” hissed Asif.

“I’m relying on it,” said Gisburne. Asif cast a bemused look at Galfrid, but the old squire remained silent and inscrutable.

The knight rallied for a moment, his face deathly pale. “I will tell you nothing,” he spat.

“I’m asking nothing,” said Gisburne, and pushed the bolt sideways.

The knight screamed again.

Asif leaned forward, his tone urgent. “We must get what information we can from him before it’s too late.”

“We’re past that point,” said Gisburne. “Draw your sword.” Without question, Asif did so. He turned his attention to the dark tunnel.

“D’you suppose I am afraid of you?” coughed the knight with all the contempt he could muster.

Gisburne gripped the man’s surcoat in his fists, and pulled him closer. “You should be,” he said.

The knight held his gaze – but for a moment his defiance seemed to falter. “Who are you?”

“Guy of Gisburne. The man who broke Castel Mercheval – and your master with it.”

Recognition dawned upon the knight’s face. “Gisburne…” He slumped back and coughed up blood. Then, inexplicably, he began to laugh. It grew in intensity, in spite of the pain it clearly caused him.

Asif stared at Galfrid in bemusement. This time, Galfrid’s face creased into a frown. The wounded knight’s left hand gripped Gisburne’s robes, and he drew himself up again. It seemed he wished to say something. Gisburne bent lower, and the man spoke, in a rasping whisper. “A red hand is coming…” With that, he began to chuckle. A mad laugh… or an exultant one.

Gisburne stared at him with incomprehension. “What do you mean?” The knight ignored the question, his laughter rising. Gisburne shook him. “What do you mean?”

The knight’s head jerked sideways with a horrid, convulsive movement, and something splattered across Gisburne’s cheek. He blinked, then saw the crossbow bolt sunk deep in the man’s temple. The knight fell back, his eyes like glass.

The bolt had come from the dark tunnel. But no sooner had they grasped this fact than their attackers were upon them – three tall figures, striding out of the gloom.

Gisburne leapt up. Two grim-faced figures – Christian knights, their swords raised – were rushing towards him. But it was not these men that commanded his attention. Between them, and a little way behind, was a third – taller, hooded, a crossbow hanging from one hand, a sword in the other, but with a face that glinted weirdly in the torchlight. At first glimpse, it seemed the fresh face of youth – pink cheeked, rosy lipped, albeit with strangely dead eyes. Then one was struck by its lack of expression, its uncanny stillness – the blank, lifeless perfection of a painted effigy.

There was one other detail – so insignificant, that any other would have missed it – but Gisburne’s eyes sought it out. The index finger of the hand that held the sword was hooked over the weapon’s crossguard. Even in the grip of onrushing threat, Gisburne felt himself shudder. This was the man they had sought these past months.

Tancred de Mercheval. The White Devil.

His bearing, the way he moved; these things were imprinted upon Gisburne’s brain. Presumably, the painted visage he now wore was meant to help him pass for a normal man when forced to traverse the streets. It so nearly succeeded – perhaps actually did so when only casually apprehended – but under close scrutiny, its strangeness seemed to grow exponentially. And yet Gisburne knew that what it hid was far, far worse – that behind this strange mask was a face distorted by mutilation, its features destroyed, its scalp denuded of flesh. A living skull.

It was a monster Gisburne himself had helped to create.

He had left the fanatical rebel Templar for dead in the smoking rubble of his own shattered castle over a year ago, his body burned by fire and quicklime. Every day since, Gisburne had cursed that one omission – had regretted that he had not made sure the job was finished, if only for the sake of those Tancred had tortured. For the sake of Galfrid.

Somehow – impossibly – Tancred had risen from that smouldering ruin. And he had not only refused to die, but had returned more dangerous, more twisted than before. There were those who claimed Tancred belonged in Heaven – more still who believed he belonged in Hell. All Gisburne knew for certain was that neither seemed to want him.

The empty holes that were the mask’s eyes bored into Gisburne’s own. “You…” hissed Tancred. He flung his crossbow aside with a clatter.

Gisburne’s was already in his hand – but before he could move, a stocky figure charged past, almost knocking him off his feet.

Galfrid.

He was flying headlong at Tancred, his pilgrim staff swinging wildly, its heavy steel head booming through the air. Galfrid was habitually measured in his actions – it did not benefit either squire or knight to be otherwise. But Gisburne had caught the look in his squire’s eye as he passed. It burned with anger and hatred. Such things blinded a man.

The knight to Galfrid’s left – entirely overlooked – swung his sword with awesome force, countering the staff long before it had a chance to connect. There was a deafening crack as the two weapons met. The staff – notched, but intact – flew from Galfrid’s grip, but was evidently far heavier than the knight had anticipated. His own sword was jarred from his hand. He fumbled, grabbing at it, but it eluded his grasp. Galfrid, still in a burning rage, flew at him, grabbing handfuls of surcoat and mail. As they tussled on the narrow walkway, Asif went for the second of the two knights. Gisburne, meanwhile, braced himself to face Tancred. But as he turned his weapon, about to strike, he saw Galfrid suddenly spun by his opponent, and both pitched sideways into the dank lagoon, stinking spray flying up as they hit.

The distraction almost cost Gisburne his life, but he was somehow was aware of Tancred’s blade as it sang through the air towards him and instinct took over. He dropped to his knees, Tancred’s sword slicing the air inches above his head, then brought his own blade up with all the force he could summon. It was an awkward blow, hastily conceived – but its edge struck Tancred square across the face. Gisburne felt metal hit metal, and fell forward, onto all fours. Tancred staggered back, a silver gash scarring the painted steel of his mask, but the tip of his sword – at the end of its great, uninterrupted arc through the air – caught the top of Asif’s skull.

Asif, who had looked like getting the better of his adversary, teetered unsteadily, a bloody flap of flesh and hair hanging where the blade had scalped him to the bone. Then his knees buckled under him and he crashed against the rock wall.

Asif’s opponent now advanced on Gisburne. Gisburne, about to clamber to his feet, saw and felt the knight’s foot stamp upon his sword blade, pinning it to the rock. His attacker’s own blade glinted high above, ready to smash down upon his head. Gisburne gazed up at him, weaponless.

With a roar, the knight struck. In an apparently futile gesture, Gisburne raised his right arm against the flashing steel blade.

The sword stopped dead with a jarring impact. Gisburne’s head remained intact. The knight stared at the blade, still resting upon Gisburne’s miraculously uninjured forearm, and his brutal features rearranged themselves into an expression of disbelief.

Gisburne grasped the moment. He thrust his forearm up and to the side, and the sword went with it, flipping out of the knight’s hands as if plucked from them by a giant’s fingers. Before his opponent could recover, he launched himself upward, smashing the top of his head into his attacker’s teeth, and slammed him against the rock wall. The knight slumped, insensible. But as Gisburne turned to retrieve his sword, the whole world suddenly seemed to shift around him.

Tancred had plucked the torch from the wall, the deep shadows shifting and dancing as it moved on its course, and now stood before him like a wraith, flame in one hand, sword in the other.

“You fought me with fire once,” he said, his voice a dry rasp. “But God’s wrath cannot be undone by earthly means. This matter that surrounds us… It is mere distraction. The Devil’s work. Corrupt flesh. And Jerusalem is its rotten heart. But it shall be revealed for what it is. It will undergo the judgement of fire.”

Then he struck. Against all expectation, he held back with the sword, and instead swung the flame. It smashed against Gisburne’s head, sparks flying. He staggered, and tried to back away. But Tancred advanced and set about him, battering him again and again with the burning torch, his eyes fleetingly visible through the dark openings of the mask, blazing in their lidless sockets. Gisburne fell to his knees, clinging this time to the rock wall, but Tancred did not stop. With each blow, sparks flew out across the oily slick, threatening to ignite it. Finally, Gisburne collapsed.

Tancred stopped and stared at the bloodied Gisburne for a moment. He poked at his enemy’s forearm with a foot, pushed back the ragged sleeve, and saw the plate metal vambrace that had stopped his knight’s sword, and the row of blunt teeth along its lower edge that had trapped its blade. Through his daze, Gisburne thought he heard a chuckle of admiration.

He blinked up at his looming adversary, the expressionless, painted face cocked to one side. “This is not the end I imagined for you,” Tancred said. His voice was grotesquely child-like, his tone almost sing-song. Never had he sounded so insane. “I had hoped for something more elaborate. But no matter. An end is an end.” He drew himself up to full height again, and sighed deeply, as if with genuine regret. “Time to burn.”

And he tossed the torch into the lake.

With a great roar, it turned into a lake of fire. In the dazzling light, Gisburne saw Tancred retreating along the tunnel. Then the wave of heat hit, robbing him of his breath. He turned back to the blazing expanse, knowing Galfrid was somewhere in it. He would not leave him. Not this time.

He heard a cry. Splashing at the edge of the ledge was Galfrid, his arm reaching up to Gisburne. As Gisburne watched, flames licked the length of it, then across Galfrid’s soaked head. He scrambled towards him, saw the desperation in his face, his mind racing. “Sorry, old man,” he said, and shoved the squire back under. Galfrid’s expression at that moment was one Gisburne would always remember. A moment later he dragged him back up by his hood and hauled him out, coughing and spluttering, the flames smothered and extinguished.

At his side, seemingly from nowhere, the great figure of Asif loomed, the flap of bloody scalp now bound up with the black material of his turban. Gisburne was never more glad to see him.

“We must leave now if we are to live!” Asif urged. “The smoke and heat will choke us!”

Gisburne began to move, then stopped. He stared through the haze at the mountain of wooden barrels. The fire had not yet spread into the tunnels, but in another few moments, the barrels would burn through and release their load. Galfrid grabbed his arm – “Come on!” – but Gisburne tore it from Galfrid’s grip.

There was no time to explain. He ripped the bolt from the dead knight’s shoulder, took up his crossbow, cocked the lever to span the bow and loaded the tethered bolt. He did not fuss with it this time – barely paused to take aim.

The bolt flew. It stuck fast in one of the barrels in the lower row. Gisburne pulled on it. It held. He wrapped the cord about the vambrace and gauntlet, and heaved. The barrel stayed where it was. The others now saw his purpose, locked arms around him and added their weight to his.

The barrel still did not move.

Flames licked about them. Gisburne could feel the air being sucked from his lungs. They had their whole combined weight pulling now. The cord was stretched to its limit – was surely about to snap. Then, as they watched, the cord caught fire and began to burn.

Hope was lost. There was nothing left for them to do, no chance of escape. Gisburne supposed there never had been much chance.

Without warning, the barrel popped out from beneath its cousins. They crashed backwards as it bounced once and flew spinning into the burning liquid. Through the smoke and heat haze, Gisburne saw several rows above the empty space shift, and stop. For a moment, nothing moved. Then, in one great rumbling motion, the entire heap collapsed into the lake.

“Brace yourselves!” bellowed Gisburne, and put his arm across his face. A great tidal wave of filth swamped them, knocking them off their feet, and hurled them hard against the rock wall. They clung on as it subsided, threatening to drag them with it.

Gisburne lay huddled for some time before he dared look – and it was only Asif’s laughter that persuaded him to do so.

The chamber was filled with thick smoke, the stinking tide of effluent slopping back and forth like a rough sea. But the flames upon its surface had been smothered.

Jerusalem would not burn tonight.

Order: UK | US | DRM-free eBook